From Black Writers of the Founding Era

Interesting Links

Benjamin Banneker: Biography and Timeline (Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum)

“Jefferson’s Notes from Condorcet on Slavery” (National Archive)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “The natural right of all Men—& their Children,” Lancaster Hill, Peter Bess, Brister Slenser, Prince Hall, et al.

• “Madison Washington,” William Wells Brown

• “A Dream,” Anonymous

Buy the book

Black Writers of the Founding Era

Black Writers of the Founding Era

767 pages

List price: $40.00

Save 30%

Web store price: $28.00

Benjamin Banneker: Biography and Timeline (Benjamin Banneker Historical Park and Museum)

“Jefferson’s Notes from Condorcet on Slavery” (National Archive)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “The natural right of all Men—& their Children,” Lancaster Hill, Peter Bess, Brister Slenser, Prince Hall, et al.

• “Madison Washington,” William Wells Brown

• “A Dream,” Anonymous

Buy the book

Black Writers of the Founding Era

Black Writers of the Founding Era767 pages

List price: $40.00

Save 30%

Web store price: $28.00

I am happy to be able to inform you that we have now in the United States a negro, the son of a black man born in Africa, and of a black woman born in the United States, who is a very respectable Mathematician. I procured him to be employed under one of our chief directors in laying out the new federal city on the Patowmac [Potomac], and in the intervals of his leisure, while on that work, he made an Almanac for the next year, which he sent me in his own handwriting, and which I inclose to you. I have seen very elegant solutions of Geometrical problems by him. Add to this that he is a very worthy and respectable member of society. He is a free man. I shall be delighted to see these instances of moral eminence so multiplied as to prove that the want of talents observed in them is merely the effect of their degraded condition, and not proceeding from any difference in the structure of the parts on which intellect depends.A decade earlier, Condorcet published Réflexions Sur L'Esclavage des Négres (Reflections on the Slavery of Negroes), a strident condemnation of slavery, and Jefferson purchased two copies of the work. Its opening preface, “Epistle dedicatory to the Negro slaves,” which Jefferson translated for himself in his personal notes, began, “Tho’ not of your colour, my friends, I have ever considered you as my brethren. Nature has endowed you with the same genius, the same judgment, the same virtues as the Whites.” When Jefferson lived in Paris between 1784 and 1789, he had known Condorcet; as biographer Fred Kaplan points out in His Masterly Pen, it’s not clear whether Condorcet and his associates knew that Jefferson was a slaveowner—or that James and Sally Hemings, the two servants staying in his hotel, were in fact enslaved by him, contrary to French law.

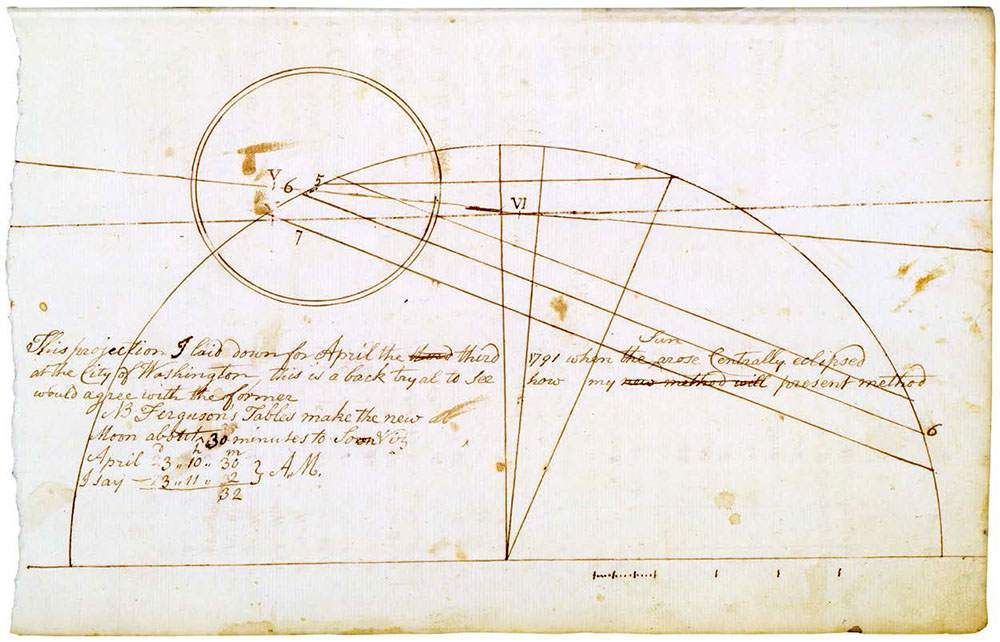

It is also not known if Condorcet ever received the manuscript sent to him by Jefferson. The French revolution had turned the city of Paris into a center of chaos, and Condorcet died in a prison three years later, probably from poisoning. The author of the manuscript in question, which featured among its calculations astronomical data and tide tables for 1792, was Benjamin Banneker, the most accomplished African American mathematician and scientist in the early history of the United States. The child of a free Black mother and a formerly enslaved father from Africa, Banneker was an autodidact with limited schooling but a lifelong intellectual curiosity. In his forties he took on astronomy and, with the support of members of the prominent Ellicott family who lived near him in rural Maryland, he was appointed to the surveying team that laid out the District of Columbia in 1791—an assignment mentioned by Jefferson in his letter to Condorcet. Banneker produced annual almanacs from 1792 to 1797 in seven cities, including Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Richmond.

When Banneker sent Jefferson the handwritten copy of his first almanac, he included a cover letter that, as he put it, took “a liberty which seemed to me scarcely allowable, when I reflected on that distinguished and dignified station in which you stand.” He chided the Secretary of State for his views on Africans and their descendants, such as those expressed in Notes on the State of Virginia (“in reason [they are] much inferior, as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigations of Euclid”), and for the hypocrisy between the professed ideas of the Declaration of Independence and the realities of slavery. Jefferson’s brief response acknowledged receipt of the manuscript and indicated he would send it to Condorcet—but he left unanswered most of the points raised in Banneker’s letter, which we reprint below. Both Banneker’s letter and Jefferson’s reply were reprinted several times, including in the Baltimore edition of his 1793 almanac and in a standalone pamphlet printed in Philadelphia.

Much of the above paragraph detailing Banneker’s biography is adapted from

Black Writers of the Founding Era (edited by James G. Basker, with

Nicole Seary).

* * *

For this week’s selection, we depart from the usual format and reproduce the selection, in its entirety, below.Letter to Thomas Jefferson

You may also download it as a PDF or view it in Google Docs.

Maryland, Baltimore County, Near Ellicotts Lower Mill, Augt 19th 1791

Thomas Jefferson Secretary of State

Sir,I am fully sensible of the greatness of that freedom which I take with you on the present occasion; a liberty which seemed to me scarcely allowable, when I reflected on that distinguished and dignified station in which you stand, and the almost general prejudice and prepossession, which is so prevalent in the world against those of my complexion.

I suppose it is a truth too well attested to you, to need a proof here, that we are a race of beings, who have long labored under the abuse and censure of the world, that we have long been seen rather as brutish than human, and scarcely capable of mental endowments.

Sir I hope I may safely admit, in consequence of that report which hath reached me, that you are a man far less inflexible in sentiments of this nature, than many others; that you are measurably friendly, and well disposed towards us, and that you are willing and ready to lend your aid and assistance to our relief from those many distresses and numerous calamities to which we are reduced.

Now, Sir, if this is founded in truth, I apprehend you will readyly embrace every opportunity, to eradicate that train of absurd and false ideas and oppinions, which so generally prevails with respect to us, and that your sentiments are concurrent with mine, which are that one universal Father hath given Being to us all, and that he hath not only made us all of one flesh, but that he hath also without partiality afforded us all the same sensations and endued us all with the same faculties, and that however variable we may be in society or religion, however diversified in situation or color, we are all of the same family, and stand in the same relation to him.

Sir, if these are sentiments of which you are fully persuaded, I hope you cannot but acknowledge, that it is the indispensible duty of those who maintain for themselves the rights of human nature and who profess the obligations of christianity, to extend their power and influence to the relief of every part of the human race, from whatever burden or oppression they may unjustly labor under, and this I apprehend a full conviction of the truth and obligation of these principles should lead all to.

Sir, I have long been convinced, that if your love for yourselves, and for those inestimable laws which preserve to you the rights of human nature, was founded on sincerity, you could not but be solicitous that every individual, of whatever rank or distinction, might with you equally enjoy the blessings thereof; neither could you rest satisfied, short of the most active diffusion of your exertions, in order to their promotions from any state of degradation, to which the unjustifiable cruelty and barbarism of men may have reduced them.

Sir, I freely and chearfully acknowledge, that I am of the African race, and in that colour which is natural to them of the deepest dye, and it is under a sense of the most profound gratitude to the supreme Ruler of the universe, that I now confess to you, that I am not under that state of tyrannical thraldom, and inhuman captivity, to which too many of my brethren are doomed; but that I have abundantly tasted of the fruition of those blessings, which proceed from that free and unequalled liberty with which you are favoured, and which I hope you will willingly allow you have mercifully receiv’d, from the immediate hand of that Being, from whom proceedeth every good and perfect gift.

Sir, suffer me to recall to your mind that time, in which the Arms and tyranny of the British Crown were exerted with every powerful effort in order to reduce you to a state of servitude: look back I entreat you on the variety of dangers to which you were exposed, reflect on that time, in which every human aid appeared unavailable, and in which even hope and fortitude wore the aspect of inability to the conflict, and you cannot but be led to a serious and grateful sense of your miraculous and providential preservation; you cannot but acknowledge, that the present freedom and tranquility which you enjoy you have mercifully received, and that it is the peculiar blessing of Heaven.

This Sir, was a time in which you clearly saw into the injustice of a state of slavery, and in which you had just apprehensions of the horrors of its condition, it was now Sir, that your abhorrence thereof was so excited; that you publickly held forth this true and invaluable doctrine, which is worthy to be recorded and remembered in all succeeding ages. “We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, and that among these are, life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Here Sir, was a time in which your tender feelings for yourselves had engaged you thus to declare, you were then impressed with proper Ideas of the great violation of liberty, and the free possession of those blessings to which you were intitled by nature; but Sir, how pitiable is it to reflect that altho you were so fully convinced of the benevolence of the Father of mankind, and of his equal and impartial distribution of these rights and privileges which he had conferred upon them, that you should at the same time counteract his mercies, in detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren under groaning captivity and cruel oppression, that you should at the same time be found guilty of that most criminal act which you professedly detested in others, with respect to yourselves.

Sir, I suppose that your knowledge of the situation of my brethren is too extensive to need a recital here; neither shall I presume to prescribe methods by which they may be relieved, otherwise than by recommending to you and all others, to wean yourselves from those narrow prejudices which you have imbibed with respect to them, and as Job proposed to his friends “Put your Souls in their Souls Stead,” thus shall your hearts be enlarged with kindness and benevolence toward them, and thus shall you need neither the direction of myself or others in what manner to proceed herein.

And now Sir, altho my sympathy and affection for my brethren hath caused my enlargement thus far, I ardently hope that your candour and generosity will plead with you in my behalf, when I make known to you, that it was not originally my design; but having taken up my pen in order to direct to you as a present, a copy of an Almanac which I have calculated for the succeeding year, I was unexpectedly and unavoidably led thereto.

This calculation Sir, is the production of my arduous study in this my advanced stage of life; for having long had unbounded desires to become acquainted with the secrets of nature, I have had to gratify my curiosity herein through my own assiduous application to Astronomical Study, in which I need not recount to you the many difficulties and disadvantages which I have had to encounter. And altho I had almost declined to make my calculation for the ensuing year, in consequence of that time which I had allotted therefor being taken up at the Federal Territory, by the request of Mr. Andrew Ellicott, yet finding myself under several engagements to Printers of this state to whom I had communicated my design, on my return to my place of residence, I industriously applyed myself thereto, which I hope I have accomplished with correctness and accuracy, a copy of which I have taken the liberty to direct to you, and which I humbly request you will favorably receive; and altho you may have the opportunity of perusing it after its publication, yet I choose to send it to you in manuscript previous thereto, that thereby you might not only have an earlier inspection, but that you might also view it in my own hand writing.

and now Sir, I shall conclude

and subscribe myself with the most profound respect

your most obedient humble servant

B Banneker

NB any communication to me may be had by direction to Mr Elias Ellicott merchant in Baltimore Town.

On August 30, 1791, writing from Philadelphia, Jefferson responded to Banneker as follows: “Sir, I thank you sincerely for your letter of the 19th instant and for the Almanac it contained. No body wishes more than I do to see such proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren, talents equal to those of the other colours of men, & that the appearance of a want of them is owing merely to the degraded condition of their existence both in Africa & America. I can add with truth that no body wishes more ardently to see a good system commenced for raising the condition both of their body & mind to what it ought to be, as fast as the imbecillity of their present existence, and other circumstance which cannot be neglected, will admit. I have taken the liberty of sending your almanac to Monsieur de Condorcet, Secretary of the Academy of sciences at Paris, and member of the Philanthropic society because I considered it as a document to which your whole colour had a right for their justification against the doubts which have been entertained of them. I am with great esteem, Sir, Your most obedt. humble servt. Th. Jefferson.”

“Letter to Thomas Jefferson” was transcribed from the manuscript, Banneker

Astronomical Journal, MS2700, Maryland Historical Society. Courtesy of the

Maryland Historical Society.

.jpg)