From American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation

Interesting Links

“The Wedding that Ignited Philadelphia” (Ken Finkel, The Philly History Blog)

“Angelina and Sarah Grimke: Abolitionist Sisters” (Carol Berkin, Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “The Two Altars; or, Two Pictures in One,” Harriet Beecher Stowe

• “This Whole Horrible Transaction,” John Quincy Adams

• “The Lover,” Harriet Ann Jacobs

• “A Dream,” Anonymous

Buy the book

American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation

American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation

Autobiography, fiction, children’s literature, poetry, oratory, & song

970 pages

List price: $55.00

Web store price: $39.50

“The Wedding that Ignited Philadelphia” (Ken Finkel, The Philly History Blog)

“Angelina and Sarah Grimke: Abolitionist Sisters” (Carol Berkin, Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “The Two Altars; or, Two Pictures in One,” Harriet Beecher Stowe

• “This Whole Horrible Transaction,” John Quincy Adams

• “The Lover,” Harriet Ann Jacobs

• “A Dream,” Anonymous

Buy the book

American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation

American Antislavery Writings: Colonial Beginnings to Emancipation Autobiography, fiction, children’s literature, poetry, oratory, & song

970 pages

List price: $55.00

Web store price: $39.50

With help from Angelina and her sister Sarah Moore Grimké, Angelina’s husband Theodore Dwight Weld published the densely packed, encyclopedic compendium of eyewitness accounts. To counter the argument by “slaveholders and their apologists” that “their slaves are kindly treated,” the three editors compiled a mountain of evidence that evinced “their condemnation out of their own mouths”:

[The] newspapers in the slaveholding states teem with advertisements for runaway slaves, in which the masters and mistresses describe their men and women, as having been ‘branded with a hot iron,’ on their ‘cheeks,’ ‘jaws,’ ‘breasts,’ ‘arms,’ ‘legs,’ and ‘thighs;’ also as ‘scarred,’ ‘very much scarred,’ ‘cut up,’ ‘marked,’ &c. ‘with the whip,’ also with ‘iron collars on,’ ‘chains,’ ‘bars of iron,’ ‘fetters,’ ‘bells,’ ‘horns,’ ‘shackles,’ &c. They, also, describe them as having been wounded by ‘buckshot,’ ‘rifle-balls,’ &c. fired at them by their ‘owners,’ and others when in pursuit; also, as having ‘notches,’ cut in their ears, the tops or bottoms of their ears ‘cut off,’ or ‘slit,’ or ‘one ear cut off,’ or ‘both ears cut off,’ &c. &c. The masters and mistresses who thus advertise their runaway slaves, coolly sign their names to their advertisements, giving the street and number of their residences, if in cities, their post office address, &c. if in the country; thus making public proclamation as widely as possible that they ‘brand,’ ‘scar,’ ‘gash,’ ‘cut up,’ &c. the flesh of their slaves; load them with irons, cut off their ears, &c.; they speak of these things with the utmost sang froid, not seeming to think it possible, that any one will esteem them at all the less because of these outrages upon their slaves; further, these advertisements swarm in many of the largest and most widely circulated political and commercial papers that are published in the slave states. The editors of those papers constitute the main body of the literati of the slave states; they move in the highest circle of society, are among the ‘popular’ men in the community, and as a class, are more influential than any other; yet these editors publish these advertisements with iron indifference.The volume reprinted hundreds of such notices, leaving the names intact. For example, one advertisement in the July 18, 1838, issue of The North Carolina Standard, a leading paper in Raleigh, reads: “TWENTY DOLLARS REWARD. Ranaway from the subscriber, a negro woman and two children; the woman is tall and black, and a few days before she went off, I burnt her with a hot iron on the left side of her face; I tried to make the letter M, and she kept a cloth over her head and face, and a fly bonnet on her head so as to cover the burn. . . . [Signed] Micajah Ricks.” In July 1836, Mississippi sheriff J. L. Jolley placed a notice in the Clinton Gazette that he had captured and jailed a man, “says his name is Josiah, his back very much scarred by the whip, and branded on the thigh and hips, in three or four places, thus (J. M.), the rim of his right ear has been bit or cut off.” (Weld and the Grimkés devoted an entire section to the cropping of ears as a form of branding and punishment.) Considered an everyday part of life to most newspaper readers in the South, the notices were a shock to many in the North.

The Grimké sisters themselves knew the ads well. They had been born in Charleston and raised among the city’s elite; the family’s home overlooked the wharves where, until 1808, thousands of enslaved Africans arrived. Their father was a wealthy slave-owner and served on the state’s top court for four decades—eventually as its chief justice. In 1819, Sarah accompanied him when he traveled to Philadelphia to obtain medical advice for a chronic and mysterious ailment. He died while seeking a rest cure on a New Jersey beach. During her stay in Philadelphia, Sarah, 26 years old at the time, had been impressed by members of the Society of Friends, and two years later she moved to the city with her recently widowed sister, Anna Grimké Frost, and became a Quaker.

Angelina, the youngest of the fourteen Grimké children, joined Sarah and Anna in Philadelphia in 1829. She met Theodore at an abolitionist meeting in New York City in 1836, and the couple were married two years later in Anna’s home, on Monday, May 14, 1838, in a ceremony for which they had written their own vows. Later that week, Sarah described the occasion in a letter to a friend:

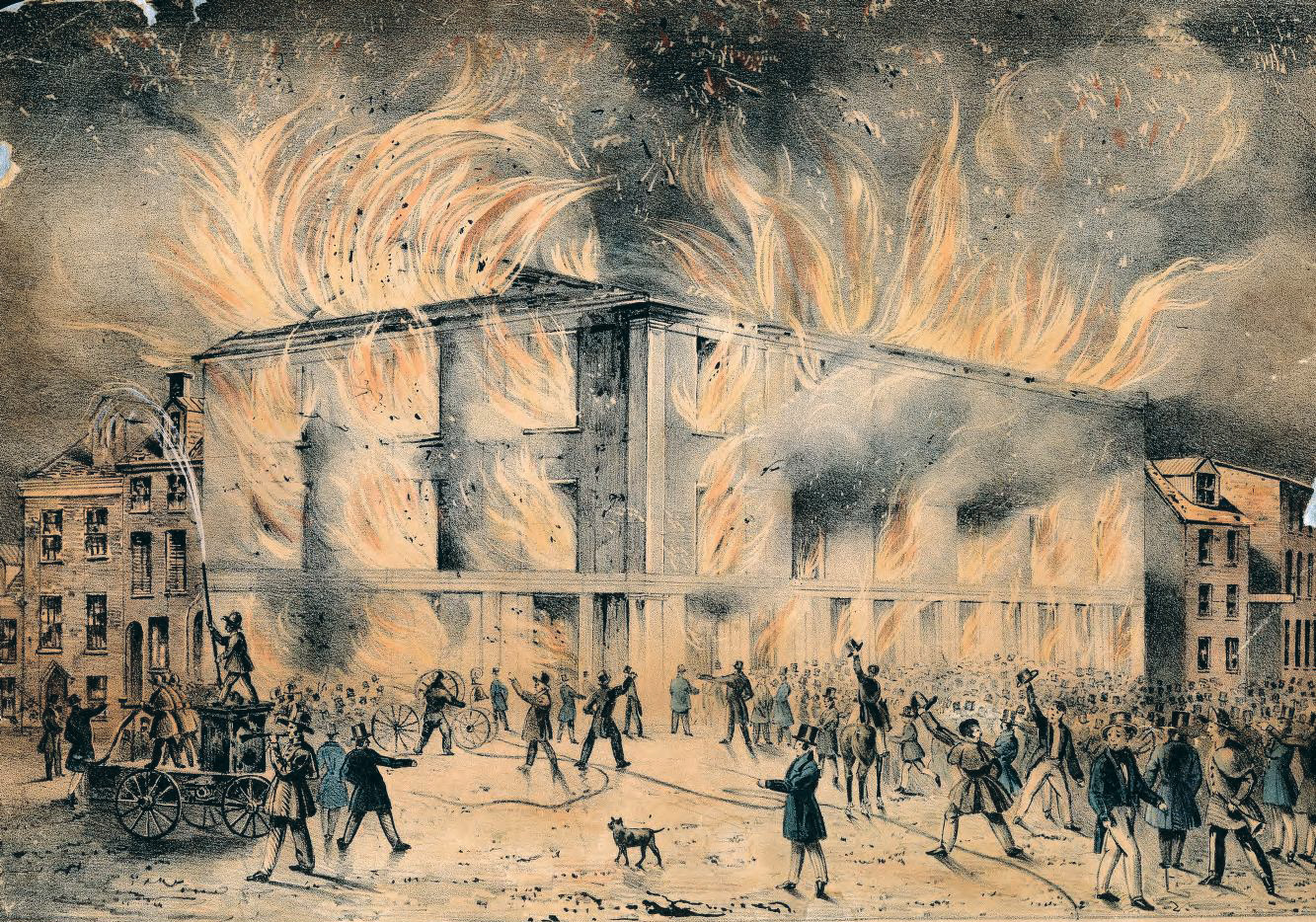

A colored Presbyterian minister then prayed, and was followed by a white one, and then I felt as if I could not restrain the language of praise and thanksgiving to Him who had condescended to be in the midst of this marriage feast, and to pour forth abundantly the oil and wine of consolation and rejoicing. The Lord Jesus was the first guest invited to be present, and He condescended to bless us with His presence, and to sanction and sanctify the union which was thus consummated. The certificate was then read by William Lloyd Garrison, and was signed by the company. The evening was spent in pleasant social intercourse. Several colored persons were present, among them two liberated slaves, who formerly belonged to our father, had come by inheritance to sister Anna, and had been freed by her. They were our invited guests, and we thus had an opportunity to bear our testimony against the horrible prejudice which prevails against colored persons, and the equally awful prejudice against the poor.The wedding proved to be the concluding event of a day of festivities to celebrate the official opening of Pennsylvania Hall; many of the nearly one hundred wedding guests had been in town for the center’s dedication ceremonies. Built primarily as a meeting place for abolitionist and other reformist associations, the Hall was the site over the next three days for the Anti-Slavery Convention of American Women. Angelina was scheduled to speak at the event on May 16 when a mob surrounded the building and eventually threw stones and other objects through the windows. She took the stage and extemporaneously began her speech, shouting over the sound of breaking glass, “What if the mob should now burst in upon us, break up our meeting and commit violence upon our persons—would this be anything compared with what the slaves endure?” She then spoke for over an hour before leading the women, double file, out of the building and safely through the stunned mob. The following night, however, proslavery forces returned and burned the building to the ground, three days after its opening, while the city’s firefighters stood by and watched.

The next year, the newlyweds, along with Sarah, moved to a small farm in New Jersey and published American Slavery As It Is. One of Sarah’s contributions to the volume was her own “Narrative and Testimony,” which recounted the horrors she had witnessed while living in Charleston and which we present below.

Note: Grimke’s essay refers to the Narrative of James Williams. Raised as a household servant to a man named George Larrimore in Virginia, Williams became a slavedriver on an Alabama plantation under the direction of a sadistic overseer. Elements of the book, ghost-written by John Greenleaf Whittier, had been doubted and disputed since its publication in 1838 because (as recent scholarship culminating in an annotated edition by Hank Trent shows) Williams had altered or romanticized many of the names, dates, places, and events in his biography—including his own name—to avoid discovery by his pursuers; the misrepresentations made factual verification impossible. In the words of one recent reviewer, it should be read for “what it is—an honest account of a runaway’s sufferings and escape using misdirection as a form of self-preservation.”

* * *

As I left my native state on account of slavery, and deserted the home of my fathers to escape the sound of the lash and the shrieks of tortured victims, I would gladly bury in oblivion the recollection of those scenes with which I have been familiar. . . . If you don't see the full selection below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!This selection may be photocopied and distributed for classroom or educational use.