From The American Revolution: Writings from the War of Independence

Interesting Links

“Benjamin Franklin Joins the Revolution,” by Walter Isaacson (Smithsonian Magazine)

“John Adams and Benjamin Franklin: Founding Fathers fall out in Paris,” by Gordon S. Wood (Reader’s Almanac)

Previous Story of the Week selections:

• “Destruction of the Tea in Boston,” John Adams

• “Account of the Battle of Monmouth,” George Washington

Buy the book

The American Revolution: Writings from the War of Independence

The American Revolution: Writings from the War of Independence

Over 120 pieces by more than seventy participants and eyewitnesses • 874 pages

List price: $40.00

Save 20%, free shipping

Web store price: $32.00

“Benjamin Franklin Joins the Revolution,” by Walter Isaacson (Smithsonian Magazine)

“John Adams and Benjamin Franklin: Founding Fathers fall out in Paris,” by Gordon S. Wood (Reader’s Almanac)

Previous Story of the Week selections:

• “Destruction of the Tea in Boston,” John Adams

• “Account of the Battle of Monmouth,” George Washington

Buy the book

The American Revolution: Writings from the War of Independence

The American Revolution: Writings from the War of IndependenceOver 120 pieces by more than seventy participants and eyewitnesses • 874 pages

List price: $40.00

Save 20%, free shipping

Web store price: $32.00

|

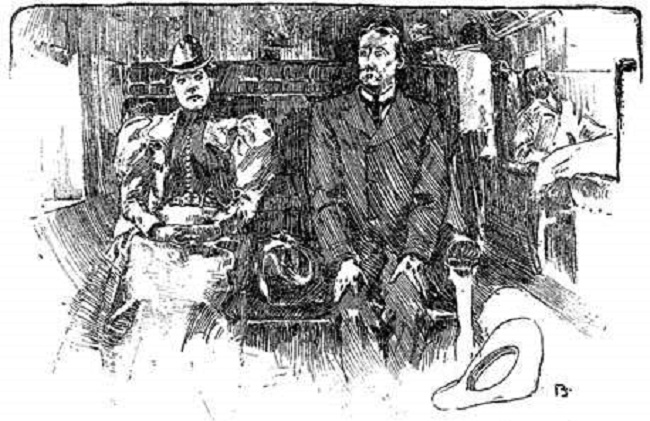

| Lady Howe Checkmating Benjamin Franklin, 1867, oil on canvas by British American artist Edward Harrison May (1824–1887). Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons. |

The following year the admiral was appointed commander of the British navy in North America. Historian Walter Isaacson summarizes what happened just after the Continental Congress issued its Declaration of Independence.

[Admiral Howe] carried a detailed proposal that offered a truce, pardons for the rebel leaders (with John Adams secretly exempted) and rewards for any American who helped restore peace.Franklin opens the following letter with a cordial statement, but the tone quickly sours as he rejects the offer with fury: “It is impossible we should think of Submission to a Government” whose “atrocious injuries have extinguished every remaining Spark of Affection for that Parent Country we once held so dear.”

Because the British did not recognize the Continental Congress as a legitimate body, Lord Howe was unsure where to direct his proposals. So when he reached Sandy Hook, New Jersey, he sent a letter to Franklin, whom he addressed as “my worthy friend.” He had “hopes of being serviceable,” Howe declared, “in promoting the establishment of lasting peace and union with the colonies.”

Congress granted Franklin permission to reply, which he did on July 30.

If you don't see the full story below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!

This selection may be photocopied and distributed for classroom or educational use.