From The Future Is Female! More Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women

Interesting Links

“Joanna Russ: When Sci-Fi Changed” (Michele Kort, Ms.)

“Sandra M. Gilbert on Joanna Russ and ‘The Barbarian’” (Library of America)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Baby, You Were Great,” Kate Wilhelm

• “The Day Before the Revolution,” Ursula K. Le Guin

• “Positive Obsession,” Octavia E. Butler

• “The New You,” Kit Reed

Buy the book

The Future Is Female! More Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women

The Future Is Female! More Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women

23 stories from the 1970s

522 pages

List price: $27.95

Web store price: $20.95

“Joanna Russ: When Sci-Fi Changed” (Michele Kort, Ms.)

“Sandra M. Gilbert on Joanna Russ and ‘The Barbarian’” (Library of America)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Baby, You Were Great,” Kate Wilhelm

• “The Day Before the Revolution,” Ursula K. Le Guin

• “Positive Obsession,” Octavia E. Butler

• “The New You,” Kit Reed

Buy the book

The Future Is Female! More Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women

The Future Is Female! More Classic Science Fiction Stories by Women23 stories from the 1970s

522 pages

List price: $27.95

Web store price: $20.95

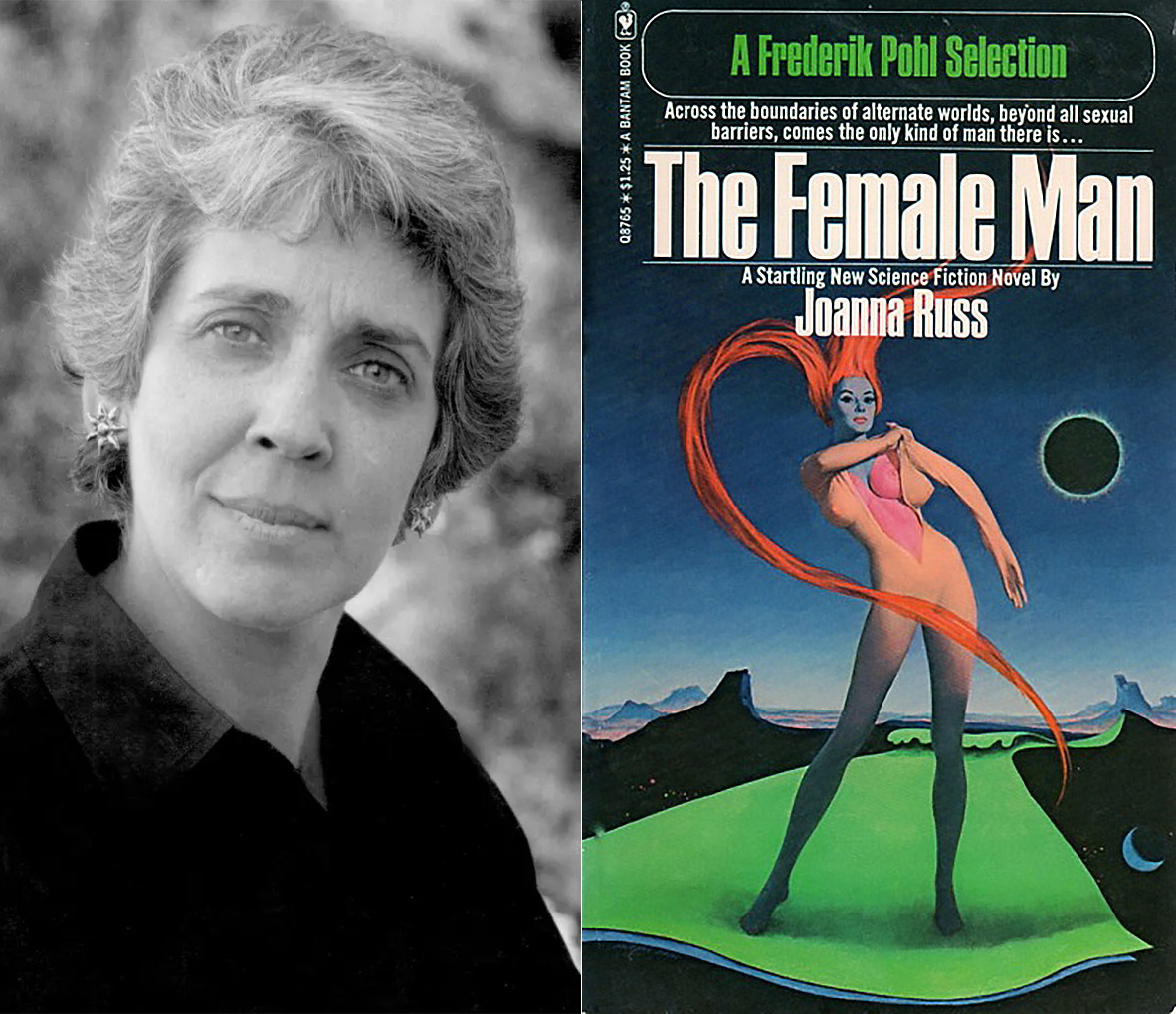

So concludes Joanna Russ’s often-reprinted essay, “The Image of Women in Science Fiction,” which first appeared in 1970 in the seventh and last issue of Red Clay Reader, a relatively obscure literary annual. Three years earlier, Russ had published her debut book, the sword-and-sorcery space adventure Picnic on Paradise, which was a finalist for the Nebula Award and a notable break from the conventions and stereotypes common in science fiction and fantasy during the previous decades. “Long before I became a feminist in any explicit way,” Russ told an interviewer in 1975, “I had turned from writing love stories about women in which women were the losers, and adventure stories about men in which men were winners, to writing adventure stories about a woman in which the woman won.”

Born and raised in the Bronx, Joanna Ruth Russ demonstrated early aptitude in the sciences and became one of the top ten finalists in the national 1953 Westinghouse Science Talent Search for her project “Growth of Certain Fungi Under Colored Light and in Darkness.” She turned to literature at Cornell, where she studied with Vladimir Nabokov (to whom she dedicated her second novel, And Chaos Died) and then earned an MFA in Playwriting from the Yale School of Drama before beginning a career as a college English professor. She sold her first science fiction story, “Nor Custom Stale,” while still in graduate school, and by the late 1960s she had established herself as a leading voice in science fiction’s New Wave. In a recent interview with Russ biographer Gwyneth Jones, Kathryn Cramer, a prominent SF editor, recalled Russ’s place in the academic and SF worlds:

Her life consisted of playing to various audiences that were difficult to reconcile. She wanted to be respected as fully as her colleagues in the English Department, even though she wrote SF. She wanted to be respected by the Radical Women for her feminist SF for which they had no use. And at the same time she wanted the respect of major figures in science fiction even though she was a woman, a lesbian, a feminist, and a socialist. She held her own there through rigor, but rigor plus depression made her a harsher critic than she wanted to be, so she eventually gave up reviewing.Russ often pointed out how frontiers had been crossed by SF in every direction: outer space and interplanetary travel, other dimensions and extraterrestrial civilizations, technological advances and human-made catastrophes, political organizations and economic systems, and even various parasciences (ESP and the like)—yet speculations on future social arrangements and the domestic sphere had been limited. “Most science fiction is set far in the future, some of it very far in the future, hundreds of thousands of years sometimes,” she wrote in her 1970 essay. “One would think that by then human society, family life, personal relations, child-bearing, in fact anything one can name, would have altered beyond recognition.” Instead, most science fiction had either carried “today’s standards and values into its future” or returned to “an idealized and exaggerated past.”

Many recent stories do show a two-sexed world in which women, as well as men, work competently and well. But this is a reflection of present reality, not genuine speculation. And what is most striking about these stories is what they leave out: the characters’ personal and erotic relations are not described; child-rearing arrangements (to my knowledge) are never described; and the women who appear in these stories are either young and childless or middle-aged, with their children safely grown up.As for the matriarchy motif that occasionally showed up in speculative fiction:

There is something about matriarchy that makes science fiction writers think of two things: biological engineering and social insects; whether women are considered naturally chitinous or the softness of the female body is equated with the softness of the “soft” sciences I don't know, but the point is often made that “women are conservative by nature” and from there it seems an easy jump to bees or ants. . . .Russ’s initial attempts to address the genre’s shortcomings are evident in two pieces of fiction she was working on at the time she wrote her essay: the Nebula Award–winning short story “When It Changed” and her pioneering masterpiece, The Female Man. Both works depict a world named Whileaway, which is populated entirely by women. When the short story appeared in Harlan Ellison’s second anthology, Again, Dangerous Visions (1972), Russ wrote in an afterword that she had read “SF stories about manless worlds before; they are either full of busty girls in wisps of chiffon who slink about writing with lust, . . . or the women have set up a static, beelike society in imitation of some presumed primitive matriarchy.” She adds, “Of SF attempts to depict real matriarchies (‘He will be my concubine for tonight,’ said the Empress of Zar coldly) it is better not to speak.”

Lisa Yaszek, who selected “When It Changed” for the just-published second volume of The Future Is Female!, points out that the story pays homage to the fictional all-female societies depicted in Mizora (1880–81) by Mary Bradley Lane and in Herland (1915) by Charlotte Perkins Gilman—that is, to “the dream of a separate space for women outside the constraints of a culture where ‘men hog the good things.’” When the poet and playwright Jewelle Gomez reviewed Russ’s 1983 collection The Zanzibar Cat, which included the story, she wrote about how “When It Changed” both defies any attempt at summarization and overcomes the wariness of some readers: “In outline this story has all the classic (i.e., dull), politically correct potential: a group of women in an independent utopia about to do battle with the enemy. On the page it is a funny, touching tale of two women who confront the problems of how to raise their children so they are not destroyed by the earth-men’s idea of sexual equality, and how their own marriage can survive.”

Notes: Parts of the above paragraph on Joanna Russ’s early life are from the biographical note in The Future Is Female!

I.C. is the abbreviation for internal combustion. Verweile doch, du bist so schoen!: “Stay a while, you are so beautiful!,” from Part 1 of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust (1808).

I.C. is the abbreviation for internal combustion. Verweile doch, du bist so schoen!: “Stay a while, you are so beautiful!,” from Part 1 of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust (1808).

* * *

Katy drives like a maniac; we must have been doing over 120 km/hr on those turns. She’s good, though, extremely good, and I’ve seen her take the whole car apart and put it together again in a day. . . . If you don't see the full selection below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!This selection is used by permission.

To photocopy and distribute this selection for classroom use, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center.

To photocopy and distribute this selection for classroom use, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center.