From Reconstruction: Voices from America’s First Great Struggle for Racial Equality

Interesting Links

“When Frederick Douglass Met Andrew Johnson” (Jennifer Szalai, The New York Times)

“Andy’s Trip”: cartoon by Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly, October 17, 1866 (HarpWeek / AndrewJohnson.com)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “The Work Before Us,” Frederick Douglass

• “They All Fired at Her,” Cynthia Townsend

• “Our Visit to Richmond,” James R. Gilmore

Buy the book

Reconstruction: Voices from America’s First Great Struggle for Racial Equality

Reconstruction: Voices from America’s First Great Struggle for Racial Equality

807 pages

List price: $40.00

Web Store price: $28.00

“When Frederick Douglass Met Andrew Johnson” (Jennifer Szalai, The New York Times)

“Andy’s Trip”: cartoon by Thomas Nast in Harper’s Weekly, October 17, 1866 (HarpWeek / AndrewJohnson.com)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “The Work Before Us,” Frederick Douglass

• “They All Fired at Her,” Cynthia Townsend

• “Our Visit to Richmond,” James R. Gilmore

Buy the book

Reconstruction: Voices from America’s First Great Struggle for Racial Equality

Reconstruction: Voices from America’s First Great Struggle for Racial Equality807 pages

List price: $40.00

Web Store price: $28.00

Through it all, Johnson faced opposition from Congress, which refused to seat senators and representatives sent by any of the new state governments, overrode his vetoes of both the Freemen’s Bureau extension and the Civil Rights Bill, and established a Joint Committee on Reconstruction to investigate conditions in the South and make recommendations concerning readmission. Hoping to turn public opinion in his favor and make electoral gains in the midterm elections, Johnson embarked on a national tour, circling the country to support congressional candidates who endorsed his agenda.

The trip started out promisingly enough: flanked by Union heroes General Ulysses S. Grant and Admiral David G. Farragut, he was cheered by tens of thousands in Baltimore and Wilmington and received a standing ovation in New York City. Things soon took a turn for the worse, however, when the party began to encounter crowds with a less favorable view of Johnson’s postwar program of pardons and reconciliation. As the number of hecklers increased, Johnson’s remarks became more ill-mannered; his extemporaneous speeches often deteriorated into shouting matches during which he denounced his opponents as traitors and compared himself to both Jesus Christ and Lincoln. “Who has suffered more for you and for this Union than Andrew Johnson?” mocked cartoonist Thomas Nast in a caricature depicting a sour-faced President with arms meekly fold across his chest and a halo over his head. Johnson’s bizarre defense against critics who accused him of betraying the Union was headlined “The President’s Trip from Springfield to St. Louis: He Denies That He Is Judas Iscariot” by The New-York Herald Tribune. “I am disgusted with this trip,” Grant told a journalist. “I am disgusted at hearing a man make speeches on the way to his funeral.” Dubbed “The Swing Around the Circle,” the tour—with the media frenzy and ridicule that resulted from it—was a complete debacle, and Republicans easily secured veto-proof majorities in both houses of Congress that fall.

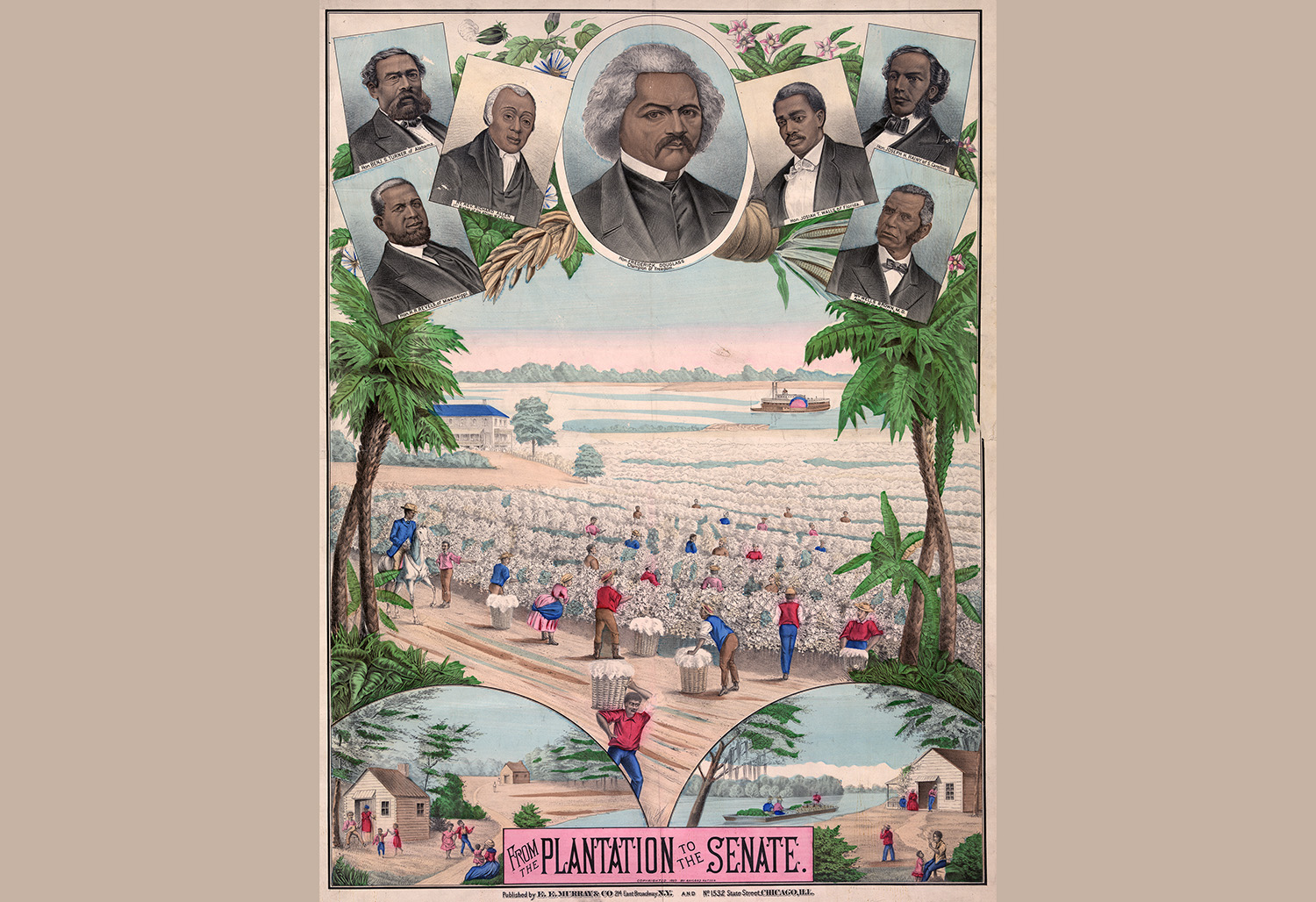

By the end of 1866, then, Congress was ready to undo everything Johnson had done and adopt its own program of reconstruction. Frederick Douglass hoped to persuade legislators—and the public—to remake the South in a manner that would protect and assist the newly freed Black population. Events that year underscored the continuing necessity of a substantial federal presence. In May, 49 people were killed when a mob attacked the homes of Black veterans in Memphis. Two months later, 34 African Americans were killed in New Orleans by opponents of the new state constitution. A small group of Confederate veterans in Tennessee—Johnson’s home state—founded the Ku Klux Klan. “Johnson discounted such acts of violence or blamed them on his opponents,” writes historian Brooks D. Simpson.

Earlier that year, Douglass had endured his own run-in with Johnson—an “interview” during which he barely got in a word while Johnson, who had no interested in listening, harangued his listeners with condescension and bluster. Like many Americans, Douglass had given up on the President. He took to the pages of The Atlantic Monthly to offer to the new Congress his recommendations for a course of action. In the December 1866 issue, he published “Reconstruction,” which summarized the events of the past year and offered a way forward; we present that article—still astonishing for its prescience—as our Story of the Week selection. “Douglass saw Reconstruction and its unprecedented challenges as a continuation of the purpose of the war, a sacred responsibility to the Union dead and to four million freed slaves,” writes David W. Blight in his recent biography.

A follow-up article, “An Appeal to Congress for Impartial Suffrage,” appeared in the next month’s issue and narrowed the focus to an explanation of why expanding the franchise and extending civil rights to Black Americans were the essential components for any reconstruction program. “The South does not now ask for slavery,” he wrote. “It only asks for a large degraded caste, which shall have no political rights.” He warned against the moral shortcomings and dangers of creating such a caste and of restricting the vote to white citizens:

It is no less a crime against the manhood of a man, to declare that he shall not share in the making and directing of the government under which he lives, than to say that he shall not acquire property and education. . . . If black men have no rights in the eyes of white men, of course the whites can have none in the eyes of the blacks. The result is a war of races, and the annihilation of all proper human relations.

* * *

Notes: The Second Session of the Thirty-ninth Congress began on December 3, 1866. Lord John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, served as British foreign secretary, 1859–65, and as prime minister, 1865–66.

* * *

The assembling of the Second Session of the Thirty-ninth Congress may very properly be made the occasion of a few earnest words on the already much-worn topic of reconstruction. . . . If you don't see the full selection below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!

This selection may be photocopied and distributed for classroom or educational use.