From Black Writers of the Founding Era

Interesting Links

“The Legacy of Isaac Royall, Jr.” (Harvard Law School)

“Massachusetts Constitution and the Abolition of Slavery” (Commonwealth of Massachusetts)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “The natural right of all Men—& their Children,” Lancaster Hill, Peter Bess, Brister Slenser, Prince Hall, et al.

• “Remember the Ladies,” Abigail Adams & John Adams

• “On the Absurdity of a Bill of Rights,” Noah Webster

Buy the book

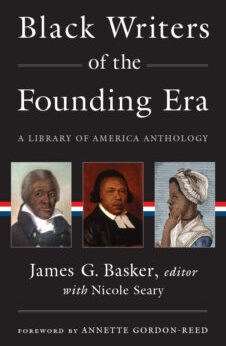

Black Writers of the Founding Era

Black Writers of the Founding Era

767 pages

List price: $40.00

Save 30%

Web store price: $28.00

“The Legacy of Isaac Royall, Jr.” (Harvard Law School)

“Massachusetts Constitution and the Abolition of Slavery” (Commonwealth of Massachusetts)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “The natural right of all Men—& their Children,” Lancaster Hill, Peter Bess, Brister Slenser, Prince Hall, et al.

• “Remember the Ladies,” Abigail Adams & John Adams

• “On the Absurdity of a Bill of Rights,” Noah Webster

Buy the book

Black Writers of the Founding Era

Black Writers of the Founding Era767 pages

List price: $40.00

Save 30%

Web store price: $28.00

|

| “Old Royall House, showing Slave Oumarters [Quarters], Medford, Mass,” c. 1906. Hand-colored photographic postcard printed by the Rotograph Company, New York. (Courtesy Royall House & Slave Quarters) |

Arguably the first slave narrative by a woman, a petition was presented to the Massachusetts legislature on February 14, 1783, by Belinda, who for fifty years had been enslaved by the landowner and businessman Isaac Royall. Born around 1713, probably in what is now Ghana or Nigeria, kidnapped at age twelve, and transported to the New World, Belinda began working for Royall and his family after they moved to Massachusetts from Antigua in 1732. Little is known of her life except that she had two children (both baptized in 1768), a son Joseph and an invalid daughter Prine, and that she was still caring for Prine when she wrote this appeal in 1783.

Meanwhile Royall, through various businesses, including trade in rum and slaves, became one of the wealthiest men in Massachusetts and an overseer of Harvard College. A Loyalist, he fled at the outbreak of the war, eventually settling in England. In 1778, he was named in the Massachusetts banishment act, which put his property at the disposal of the state and gave Belinda hope for her petition.

In her pioneering request for reparations, Belinda’s personal travails during fifty years of enslavement are visible beneath the embellishments of the amanuensis who transcribed her story. The government ordered Royall’s executors to pay her a pension of £15, 12s. But within a year the payments had stopped. Belinda would petition again in 1785, 1787, 1788, 1790, and 1793. The second text reprinted here, more businesslike and direct, is her petition from 1793, using what is presumably her married name of Sutton. The “Sir Wm Pepperell” who cut her off was Isaac Royall’s son-in-law. The name of the executor of Royall’s estate, Willis Hall, appears at the bottom of the petition, along with “Priscilla Sutton,” who may be Belinda’s invalid daughter Prine. A clerk’s note on the backside of the docket indicates that the state had to re-enforce the pension order yet again two years later, on February 25, 1795.

Versions of her story circulated in the antislavery press of the 1780s, before disappearing. The quiet heroism of her life resurfaced in the twenty-first century, when the disgrace of her treatment led Harvard University to remove the symbols of Isaac Royall’s patronage from the insignia of its Law School, which had been partially founded with proceeds from his estate.

Notes: The Rio da Valta is the Volta River, in what is now Ghana. Orisa is a deity or spirit in the Yoruba language and religion.

* * *

The Petition of Belinda an Affrican, humbly shews that seventy years have rolled away, since she on the banks of the Rio da Valta, received her existence. . . . If you don't see the full selection below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!This selection may be photocopied and distributed for classroom or educational use.