From Ernest Hemingway: The Sun Also Rises & Other Writings 1918–1926

Interesting Links

“Biography | Hadley Richardson” (Ken Burns’s Hemingway, PBS)

“How Hemingway became Hemingway” (Jennifer Hunter, Toronto Star)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Cat in the Rain,” Ernest Hemingway

• “The Lees of Happiness,” F. Scott Fitzgerald

• “Tom’s Husband,” Sarah Orne Jewett

Buy the book

Ernest Hemingway: The Sun Also Rises & Other Writings 1918–1926

Ernest Hemingway: The Sun Also Rises & Other Writings 1918–1926

in our time (1924) | In Our Time (1925) | The Torrents of Spring | The Sun Also Rises | journalism | letters | 863 pages

List price: $35.00

Web Store price: $28.00

“Biography | Hadley Richardson” (Ken Burns’s Hemingway, PBS)

“How Hemingway became Hemingway” (Jennifer Hunter, Toronto Star)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Cat in the Rain,” Ernest Hemingway

• “The Lees of Happiness,” F. Scott Fitzgerald

• “Tom’s Husband,” Sarah Orne Jewett

Buy the book

Ernest Hemingway: The Sun Also Rises & Other Writings 1918–1926

Ernest Hemingway: The Sun Also Rises & Other Writings 1918–1926in our time (1924) | In Our Time (1925) | The Torrents of Spring | The Sun Also Rises | journalism | letters | 863 pages

List price: $35.00

Web Store price: $28.00

|

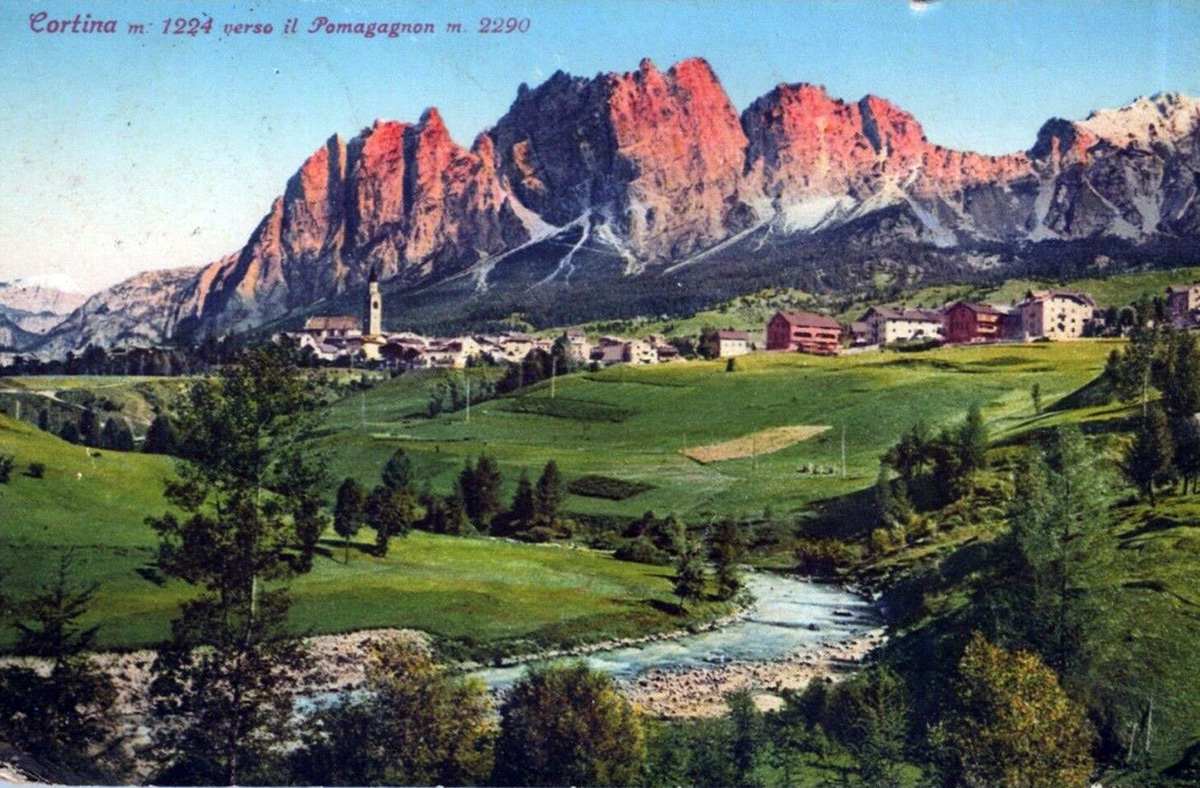

| Hand-colored photographic postcard showing Cortina d’Ampezzo during the 1920s, with the cliffs of Pomagagnon in the background. (eBay) |

I had never seen anyone hurt by a thing other than death or unbearable suffering except Hadley when she told me about the things being gone. She had cried and cried and could not tell me. I told her that no matter what the dreadful thing was that had happened nothing could be that bad, and whatever it was, it was all right and not to worry. We would work it out. Then, finally, she told me. . . . It was probably good for me to lose early work and I told [editor Edward J. O’Brien] all that stuff you feed the troops. I was going to start writing stories again I said and, as I said it, only trying to lie so that he would not feel so bad, I knew that it was true.Only two manuscripts (the stories “My Old Man” and “Up in Michigan,” each of which were elsewhere) survived the debacle.

During the following months, the couple attempted to put this incident behind them by skiing the slopes of the Alps and going on a walking tour from Milan to Cortina d’Ampezzo. In February or March, Hadley realized she was pregnant, and arguments over whether they were ready to become parents may have increased tensions between the couple. Their journey and the strains in their marriage inspired Hemingway to work on two stories during this period. First, in the seaside town of Rapallo, he scribbled four pages of notes for a story that, a year later, would become “Cat in the Rain.” Then, in April, while he and Hadley were staying in the alpine town of Cortina d’Ampezzo, he finished the story “Out of Season,” which would appear that summer alongside his two surviving stories in his first book, Three Stories and Ten Poems. He would also include the story in his 1925 collection, In Our Time.

On Christmas Eve 1925, Hemingway wrote to F. Scott Fitzgerald, whom he had met earlier in the year. Fitzgerald and his wife, Zelda, both thought the woman in “Cat in the Rain” was Hadley, which Hemingway denied, claiming that the story brought together various characters and places encountered during their trip—a hotel in Rapallo, an innkeeper in Cortina d’Ampezzo, and a couple they met in Genoa. Instead, Hemingway insisted:

The only story in which Hadley figures is Out of Season which was an almost literal transcription of what happened. Your ear is always more acute when you have been upset by a row of any sort, mine I mean, and when I came in from the unproductive fishing trip I wrote that story right off on the typewriter without punctuation. I meant it to be tragic about the drunk of a guide because I reported him to the hotel owner — the one who appears in Cat In The Rain — and he fired him and as that was the last job he had in the town and he was quite drunk and very desperate he hanged himself in the stable. At that time I was writing the In Our Time chapters and I wanted to write a tragic story without violence. So I didnt put in the hanging. Maybe that sounds silly. I didnt think the story needed it.Three decades later, in A Moveable Feast, Hemingway reiterated, “I had omitted the real end of it which was that the old man hanged himself.”

As Hemingway scholar Paul Smith notes in his essay on the story, the surviving typescript seems to confirm Hemingway’s recollection that he wrote the story immediately after returning to the hotel: “With his memory for dialogue sharpened by an abrasive row with Hadley—or Tiny, as he nicknamed her then—he wrote in too much of a hurry to pause over punctuation, especially during the writing of the couple’s bitter dialogue in the Concordia, which he did not bother to paragraph.” He later made several additions and revisions to the story—but none to the dialogue between husband and wife. If the first part of his recollection is true, however, the subsequent suicide of the guide is not something he could have omitted when he wrote the first draft but, at most, a tragedy he chose not to add to the story during its revision.

In sum, the tale as originally written is ostensibly about a fishing trip led by a drunken and comically impertinent guide scorned by his fellow townspeople, but its underlying portrait is of a couple during the hours after a heated argument. In his biography of Hemingway, Carlos Baker writes that the story’s dual nature marks a turning point in Hemingway’s career:

Ernest later spoke of it as a "very simple story." It was not. . . .Whether “Cat in the Rain” and “Out of Season” portray “Hemingway’s own marriage seems of less moment than that the subject of marriage inspired his return to fiction in 1923,” writes Smith in The Cambridge Companion to Ernest Hemingway. The stories can be said to have relaunched Hemingway’s writing career; as Gioia Diliberto, in her biography of Hadley, remarks: “The successful completion of ‘Out of Season’ eased his anguish over the lost manuscripts, for he knew that it was much better than any of the material that had been lost.”

With this story, in fact, he discovered for the first time the infinite possibilities of a new narrative technique. This consisted in developing two intrinsically related truths simultaneously, as a good poet does with a metaphor that really works. The "out-of-season" theme applied with equal force to the young man's relations with his wife Tiny, and to the officious insistence by the guide Peduzzi that the young man fish for trout in defiance of the local fishing laws. . . . The metaphorical confluence of emotional atmospheres . . . was what gave the story its considerable distinction. This first successful use of it was the foremost esthetic discovery of Ernest's early career. It was in this, rather than in the flat and uninspired verse of which he seemed so proud, that his true gifts as a poet were to be repeatedly displayed.

Notes: A musette is a small knapsack. In 1922, while covering the International Economic Conference in Genoa, Hemingway visited the humorist and caricaturist Max Beerbohm at his home outside Rapallo; he was accompanied by the American writer Max Eastman and the British journalist George Slocombe, and Beerbohm greeted his guests with glasses of marsala. With the allusion to Beerbohm’s preference for marsala, “Hemingway was able to characterize the young gentleman as, perhaps, a bit of a dandy and maybe a bit self-absorbed,” suggests literary scholar Charles J. Nolan, Jr. The Carleton Club is a gentlemen’s club in London favored by Conservative leaders.

Foreign expressions: Was Wollen sie? (German: What do you want?); vecchio (Italian: an old man); caro (Italian: dear, dear one)

Foreign expressions: Was Wollen sie? (German: What do you want?); vecchio (Italian: an old man); caro (Italian: dear, dear one)

* * *

On the four lire Peduzzi had earned by spading the hotel garden he got quite drunk. . . . If you don't see the full selection below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!This selection may be photocopied and distributed for classroom or educational use.