From Bernard Malamud: Novels and Stories of the 1970s & 80s

Interesting Links

“Mercilessness Clarifies: On Bernard Malamud” (Chris Bachelder, The Paris Review); includes audio recording of Malamud reading his story “The Silver Crown”

“A Daughter Chooses Her Favorite Bernard Malamud Story” (Janna Malamud Smith, Library of America)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Idiots First,” Bernard Malamud

• “Patrimony,” Philip Roth

• “Those Are as Brothers,” Nancy Hale

Buy this book

Bernard Malamud:

Bernard Malamud:

Novels and Stories of the 1970s & 80s

The Tenants | Dubin’s Lives | God’s Grace | 13 stories

List price: $45.00

Web Store price: $32.00

“Mercilessness Clarifies: On Bernard Malamud” (Chris Bachelder, The Paris Review); includes audio recording of Malamud reading his story “The Silver Crown”

“A Daughter Chooses Her Favorite Bernard Malamud Story” (Janna Malamud Smith, Library of America)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Idiots First,” Bernard Malamud

• “Patrimony,” Philip Roth

• “Those Are as Brothers,” Nancy Hale

Buy this book

Bernard Malamud:

Bernard Malamud:Novels and Stories of the 1970s & 80s

The Tenants | Dubin’s Lives | God’s Grace | 13 stories

List price: $45.00

Web Store price: $32.00

|

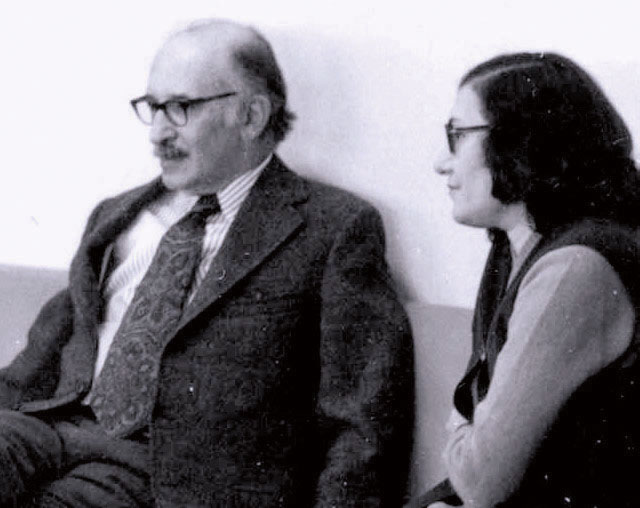

| Bernard Malamud and Cynthia Ozick, backstage before his debut reading of “The Silver Crown” at the 92nd Street Y, New York City, November 6, 1972. Photographer unknown. Image via The Paris Review. |

In 1976 I answered the telephone and heard privately an instantly recognizable public voice. I knew this voice with the intimacy of passionate reverence. I had listened to it in the auditorium of the 92nd Street Y reading an as yet unpublished tale called “The Silver Crown,” a story so electrifying that I wished with all my heart that it was mine. Since it was not, I stole it. In my version, I described the author of the stolen story as “very famous, so famous that it was startling to see he was a real man. He wore a conventional suit and tie, a conventional haircut and conventional eyeglasses. His whitening mustache made him look conventionally distinguished. He was not at all as I had expected him to be—small and astonished, like his heroes."Ozick is being somewhat modest in her reminiscence. She was not merely a member of the audience at the reading; having already published her first novel and a well-received collection of stories, she introduced Malamud to the crowd. In addition, the novella she refers to, “Usurpation (Other People’s Stories),” was, of course, no act of theft but was a homage of sorts, about a young author who hears a reading by a famous older writer at the 92nd Street Y and feels that the story (summarized and retitled by Ozick as “The Magic Crown”) is one she should have written. When she learns that the famous author himself has “usurped” the story from an item in the newspaper, she haughtily argues that had she seen the article first she would have written something different: “I would have fingered out the magical parts. Magic—I admit it—is what I lust after.” Ozick then conjures a series of interwoven tales her imaginary narrator might have created. As Ozick explains in a preface to the book that contained the story, “Belief in idols is belief in magic. And storytelling, as every writer knows, is a kind of magic act.” Ozick’s novella, then, cautions that “story-making” can be “a corridor to the corruption and abominations of idol-worship, of the adoration of magical event.”

His voice on the telephone was also not what I had expected. Instead of bawling me out for usurping his story, he was calling me with something else in mind. He had noticed that the dedication to a collection containing the stolen story was to my daughter, who was then ten years old. “Joy of my life,” I had written. “I have to tell you,” he said, “that I understand just how you feel.” And he spoke of his own joy in being the father of his own children. . . .

There is little in the way of actual “magic” in Malamud’s story; the newspaper article he “usurped” is real enough. From The New York Times, October 14, 1971:

A 68‐year‐old Orthodox rabbi and three of his relatives were indicted in the Bronx yesterday on charges that they took money for cabalastic faith‐healing rituals that never took place.Before Malamud read his short story at the 92nd St. Y in New York, he described himself as the kind of writer who finds inspiration in the smallest items or incidents. The “simple donnée” for his tale was found in the newspaper article: “the story of a rabbi that immediately burst into fiction in my mind.” In “The Silver Crown,” Malamud transforms the basic facts of the case into an exploration of the chasm between belief and skepticism, between storytelling and reality, and (in the end) between a father’s love for his daughter and a son’s disdain for his father.

As unfolded by Burton B. Roberts, the Bronx District Attorney, the indictments told of people paying as much as $1,387 for health‐restoring silver crowns that were never made. . . . Mr. Roberts said his investigation began last spring when a number of rabbis came to his office, bringing with them members of their congregations who they charged had been gulled. . . .

Articles about the rabbi began appearing in newspapers. One of these, Mr. Roberts said, was seen in Miami by a young man whose father was in a coma. The young man, who was identified only as a holder of a master's degree, visited the rabbi and asked that his father be saved from death. According to the prosecutor, the supplicant was told to bring 401 silver dollars, which would be used to fashion a crown representing the health of his father. In addition, he was allegedly told, the cost of making such a crown varied in proportion to how much the ailing person meant to the man pleading for his cure. Mr. Roberts said the applicant paid $986, for the most expensive crown.

Notes: Austro-Hungarian writer and political activist Theodor Herzl (1860–1904) founded the Zionist Organization, now the World Zionist Organization. The Mishna is the rabbinically edited compilation of Jewish oral traditions. Kabbalah is wisdom or esoteric knowledge concerned with the essence of God. The commentaries known as the Zohar are the foundations of Kabbalah. The Torah, or Pentateuch, comprise the five books of Moses from Genesis to Deuteronomy—handwritten on scrolls, rolled around two wooden staffs, and treasured in the Ark of each synagogue.

Yiddish expressions: shpeter: later; dovening, or davening, from davnen: prayer, recitation of prayer; grubber yung: a coarse youth; sha: quiet.

Yiddish expressions: shpeter: later; dovening, or davening, from davnen: prayer, recitation of prayer; grubber yung: a coarse youth; sha: quiet.

* * *

Gans, the father, lay dying in a hospital bed. Different doctors said different things, held different theories. . . . If you don't see the full selection below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!This selection is used by permission. To photocopy and distribute this selection for classroom use, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center.