From Where the Light Falls: Selected Stories of Nancy Hale

Interesting Links

“An Author Who Wrote All about, and for, Flawed Women” (S. Joyce-Farley, Library of America)

“Nancy Hale, At Last” (Maya Chung, Public Books)

“Light a Torch for Freedom!” (Amy Harrell, Mary Mahoney, and Joelle Thomas, Trinity College)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “The Earliest Dreams,” Nancy Hale

• “Old Flaming Youth,” Jean Stafford

• “A Southern Landscape,” Elizabeth Spencer

• “The Ice Palace,” F. Scott Fitzgerald

Buy the book

Where the Light Falls: Selected Stories of

Where the Light Falls: Selected Stories of

Nancy Hale

Now available in paperback

25 stories • 372 pages

“An Author Who Wrote All about, and for, Flawed Women” (S. Joyce-Farley, Library of America)

“Nancy Hale, At Last” (Maya Chung, Public Books)

“Light a Torch for Freedom!” (Amy Harrell, Mary Mahoney, and Joelle Thomas, Trinity College)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “The Earliest Dreams,” Nancy Hale

• “Old Flaming Youth,” Jean Stafford

• “A Southern Landscape,” Elizabeth Spencer

• “The Ice Palace,” F. Scott Fitzgerald

Buy the book

Where the Light Falls: Selected Stories of

Where the Light Falls: Selected Stories ofNancy Hale

Now available in paperback

25 stories • 372 pages

|

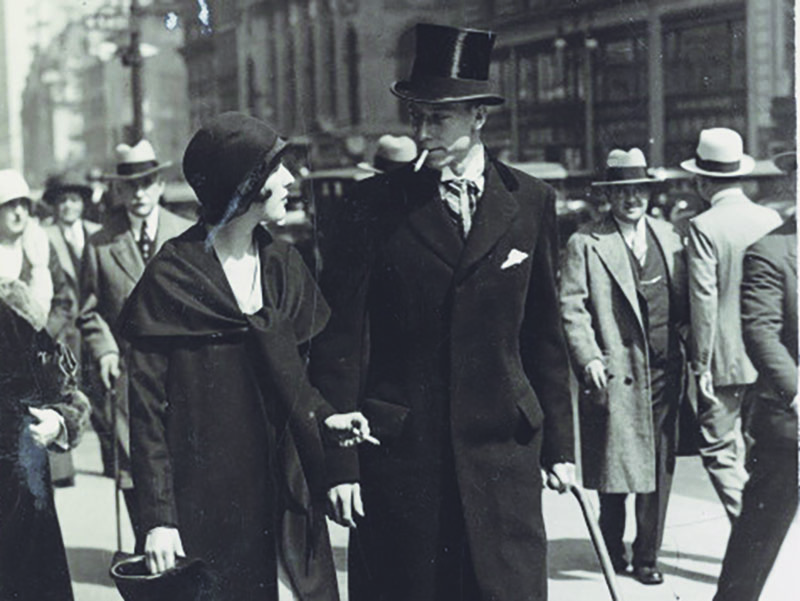

| Nancy Hale and Taylor Scott Hardin at the Easter Day Parade, Fifth Avenue, New York, 1929. (Library of Congress, via the Trinity College website). |

One of the hired models was eighteen-year-old Nancy Hale (no relation to Ruth), the only child of two prominent, bohemian artists from families whose ancestry included Harriet Beecher Stowe and Edward Everett Hale. She admitted to her mother that she was in it for the money: $10 for agreeing to be photographed and, later, “$100 for signing my name to some sort of letter they are going to send to the editors of magazines asking them to give the idea of smoking on the street publicity. . . . Pretty soft way to make money, isn’t it?” She had married Taylor Scott Hardin months earlier, and the newlyweds were photographed strolling down Fifth Avenue, cigarettes—er, torches of freedoms—in their hands.

In the introduction to Library of America’s reissue of Nancy Hale’s third novel, The Prodigal Women, Kate Bolick details Bernays’s cynical ploy and remarks, “It was precisely this sort of contradiction—the gap between what liberation looks like and what it actually is—that Hale often mined in her fiction.” Or, as her granddaughter Norah Hardin Lind writes, “She exposed the requirements for change of the era’s women and the conflicts inherent in expressing those goals.” Hale’s depictions of those conflicts and contradictions clearly appealed to women—and men—working on the home front during World War II; The Prodigal Women would end up on The New York Times Best Sellers list for 23 weeks during late fall and winter of 1942–43.

When asked by a New York Times reporter at the time why she “specialized in analyzing women” in her fiction, Hale responded drily, “That's quite interesting, because I suppose that I have specialized in women. . . . I feel that I know men quite thoroughly, that I know how, in a given situation, a man is apt to react. But women puzzle me.” She revisited this theme later in the interview:

Women’s fears are really terribly interesting. They are changing. They used to be so afraid of being run over or having a baby, and now that they are out in the world, going about on their own so much, some of the old fears are dying out and new ones are taking their places. . . . Perhaps the dominant fear now is the fear of being afraid, which probably means that they are moving farther toward maturity.Less than a year after the Torches of Freedom stunt, Nancy Hale gave birth in Virginia to her first son; during her pregnancy, she stayed with her mother-in-law, and she adapted this experience for two of her more notable short stories. “To the Invader” (1933), which won the first of her ten O. Henry Awards, describes the geographical clash in attitudes when the narrator accompanies her husband to Virginia, with its “army of semi-tropic mothers,” and endures the old-fashioned judgments, duplicitous solicitude, and barely disguised hostility of his relatives. When her mother-in-law asks if she is expecting, the young woman answers that she is pregnant, in response to which “Mrs. Augustine coughed. That meant the word wasn’t a nice one.” Her hosts recall the only other time a Northern woman married into the family, two decades earlier; she walked the local roads alone at night and “was always off consortin’ with her Bohemian friends,” even after she gave birth to her son, and so they decided “she was, well, not quite sane” and had her committed to an asylum.

The second story, “The Bubble” (1954), revisits a similar scenario from an entirely different angle, when a young woman stays (by choice, this time) with her mother-in-law in Washington during the final months of her pregnancy, in order to get away from the heady excitement of New York—and, not incidentally, to avoid letting her friends see her less-than-svelte condition. The story pits “treasured bonds of marriage and motherhood against the era’s youthful hedonism,” writes Lind, and we present it below as our Story of the Week selection.

* * *

Now when Eric was born in Washington, D.C., I was eighteen, and most people thought I was too young to be having a baby. . . . If you don't see the full selection below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!This selection is used by permission.

To photocopy and distribute this selection for classroom use, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center.

To photocopy and distribute this selection for classroom use, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center.