From O. Henry: 101 Stories

Interesting Links

“The Man Who Invented Manhattan” (Judith Dunford, American Heritage)

“Why O. Henry is so much more than those short stories you had to read in school” (Michael Dirda, The Washington Post)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “A Retrieved Reformation,” O. Henry

• “My Robin,” Frances Hodgson Burnett

• “The Young Immigrunts,” Ring Lardner

• “Dalyrimple Goes Wrong,” F. Scott Fitzgerald

Buy the book

O. Henry: 101 Stories

O. Henry: 101 Stories

840 pages

List price: $35.00

Web Store price: $30.00

“The Man Who Invented Manhattan” (Judith Dunford, American Heritage)

“Why O. Henry is so much more than those short stories you had to read in school” (Michael Dirda, The Washington Post)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “A Retrieved Reformation,” O. Henry

• “My Robin,” Frances Hodgson Burnett

• “The Young Immigrunts,” Ring Lardner

• “Dalyrimple Goes Wrong,” F. Scott Fitzgerald

Buy the book

O. Henry: 101 Stories

O. Henry: 101 Stories840 pages

List price: $35.00

Web Store price: $30.00

“There are two kinds of grafts,” said Jeff, “that ought to be wiped out by law. I mean Wall Street speculation, and burglary.”O. Henry’s fiction about the underworld was informed by the acquaintances he made in the Ohio penitentiary where he served a three-year sentence for embezzlement; most of the inhabitants, particularly those convicted of nonviolent offenses, seemed to him no worse than the Gilded Age robber barons who lived in their mansions. More often than not, O. Henry’s scam artists, burglars, and pickpockets are portrayed comically and even sympathetically; there is honor among his thieves, and under the tough-guy, semiliterate veneer are basically decent men just waiting for their moment—like the former safe-cracker in “A Retrieved Reformation.” Even the grafter Jeff Peters follows a distorted code of “ethics”: “I never believed in taking any man’s dollars unless I gave him something for it—something in the way of rolled gold jewelry, garden seeds, lumbago lotion, stock certificates, stove polish or a crack on the head to show for his money.”

“Nearly everybody will agree with you as to one of them,” said I, with a laugh.

“Well, burglary ought to be wiped out, too,” said Jeff; and I wondered whether the laugh had been redundant.

“A burglar who respects his art always takes his time before taking anything else,” claims the narrator of “Makes the Whole World Kin,” the O. Henry tale in which an intruder confronts the owner of the home he is robbing and ends up discussing various ailments for the rheumatism that afflicts them both. The criminal in “Tommy’s Burglar” (1905) experiences a similar encounter in a Manhattan brownstone—this time with a young boy—but not only does the thief abandon his original plan, the story itself goes off the rails. Prompted by the boy, the burglar “takes his time” undermining the telling of his latest caper.

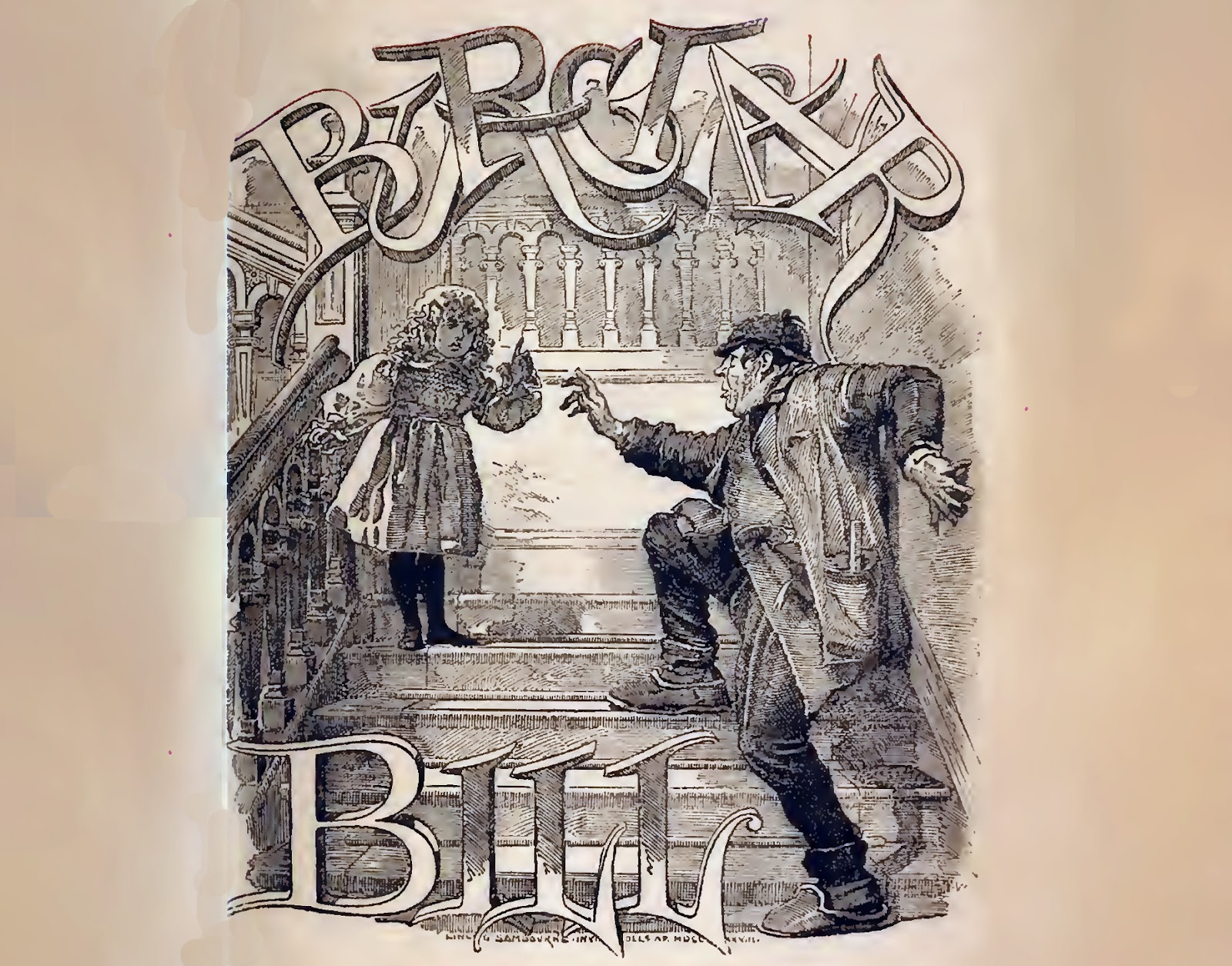

Two decades earlier, in 1881, Frances Hodgson Burnett (the author of The Secret Garden and A Little Princess) published the story “Editha’s Burglar” in the American children’s magazine St. Nicholas. An illustrated book version appeared in 1888 on the heels of her first best seller, Little Lord Fauntleroy; the story was adapted several times for the stage in both London and New York and eventually expanded to The Burglar, a four-act play by Augustus Thomas with Maurice Barrymore in the title role. Editha’s Burglar was widely imitated in children’s magazines—and was just as widely parodied. The best known of these at the time was written by Punch contributor F. Anstey (the pen name of Thomas Anstey Guthrie), who published “Burglar Bill,” a playlet in verse that deftly mocks the idea of a burglar overcome by the kindness of a little girl (“Go away!” he whimpers hoarsely, / “Burglars hev their bread ter earn. / I don't need no Gordian angel / Givin' of me sech a turn!”)

In the book version of Editha’s Burglar, seven-year-old Editha encounters a prowler (“If you please,” she said with great delicacy, “are you really a burglar?”) and, with her father away from home for the night, asks him politely if he could go about his business as quietly as possible to avoid waking up her mother. By the end of the book, the burglar is captured and imprisoned, but chastened and reformed.

O. Henry takes the premise of the Burnett story—a burglar encountering a child while the father is away and the mother is sleeping—and transforms it into a story about writing a story, skewering both the mawkish romances that dominated children’s literature and the 2,000-word tales he was contractually required to write every week for the New York Sunday World. While all the other parodies of Editha’s Burglar are lost to the dustbin of literature, O. Henry’s story is still read and anthologized in no small part because readers entirely unaware of the original children’s story can enjoy it.

Notes: St. George Rathborne was an American author known for adventure stories and dime novels. Polish tenor Jean de Reszke retired from performing in 1903, two years before the story ostensibly takes place. Italian tenor Enrico Caruso made his American debut at the Metropolitan Opera in 1903, and he was regarded as de Reszke’s successor. Tony Pastor was an American vaudeville impresario. Parsifal is an opera by Richard Wagner. Benjamin Sayre Cory Kilvert was a Canadian-born illustrator known for his depictions of children. O. Henry refers to the unities, a theory, derived from Aristotle, that a play should have a single action occurring in a single place and within the course of a single day. The S.P.C.C. is the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, founded in New York in 1874.

* * *

At ten o’clock p.m. Felicia, the maid, left by the basement door with the policeman to get a raspberry phosphate around the corner. . . . If you don't see the full selection below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!This selection may be photocopied and distributed for classroom or educational use.