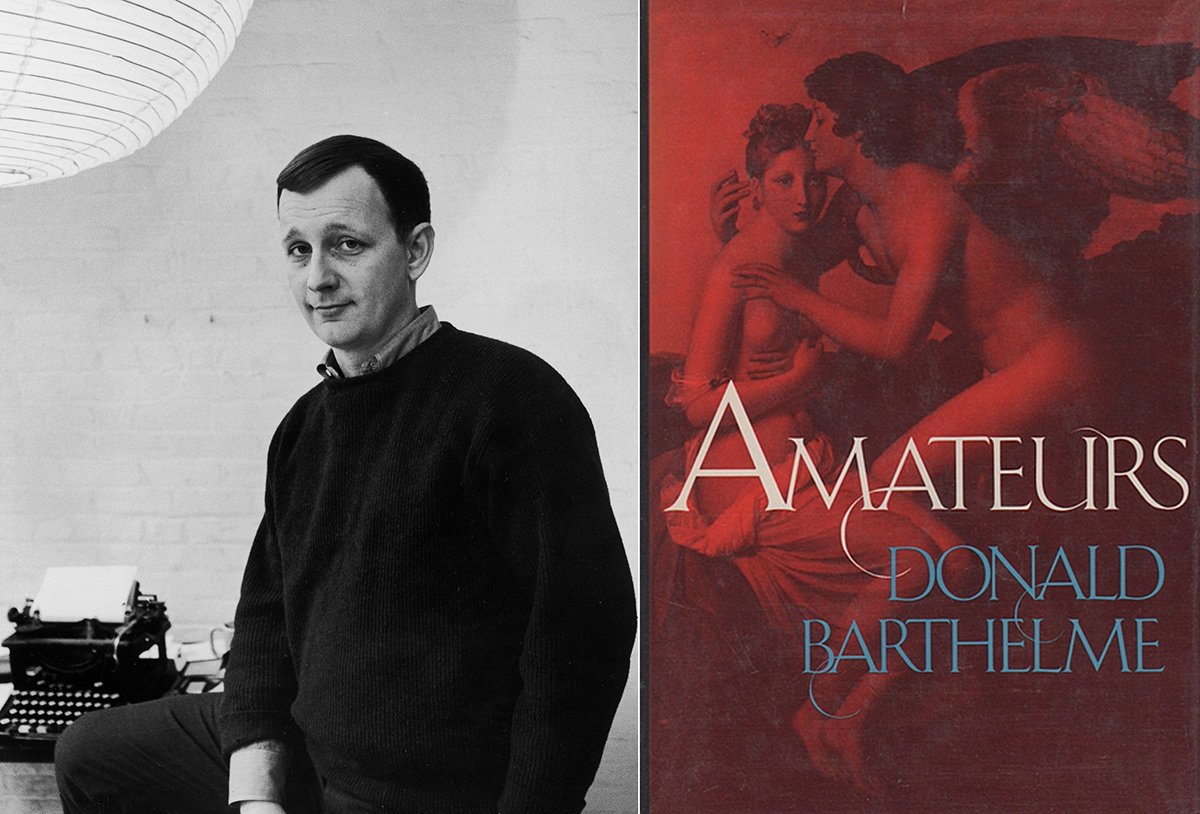

From Donald Barthelme: Collected Stories

Interesting Links

Interview: Charles McGrath on the fiction of Donald Barthelme — “You’re not reading your grandfather’s short story” (Library of America)

“Stories We Love: Donald Barthelme’s ‘The School,’ In Which is Revealed the Meaning of Life” (Michael Byers, Fiction Writers Review)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Tickets,” Donald Barthelme

• “Shiftless Little Loafers,” Susan Orlean

• “The Day the Dam Broke,” James Thurber

• “The Night We All Had Grippe,” Shirley Jackson

Buy the book

Donald Barthelme: Collected Stories

Donald Barthelme: Collected Stories

145 stories | 1,004 pages

List price: $45.00

Web Store price: $29.25

Interview: Charles McGrath on the fiction of Donald Barthelme — “You’re not reading your grandfather’s short story” (Library of America)

“Stories We Love: Donald Barthelme’s ‘The School,’ In Which is Revealed the Meaning of Life” (Michael Byers, Fiction Writers Review)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Tickets,” Donald Barthelme

• “Shiftless Little Loafers,” Susan Orlean

• “The Day the Dam Broke,” James Thurber

• “The Night We All Had Grippe,” Shirley Jackson

Buy the book

Donald Barthelme: Collected Stories

Donald Barthelme: Collected Stories145 stories | 1,004 pages

List price: $45.00

Web Store price: $29.25

It may be the sincerest form of flattery, but sometimes imitation takes bizarre turns, which caused Barthelme to publish a short note in the letters section of The New York Times Book Review at the end of 1973:

The fall 1973 number of the Carolina Quarterly contains a story called “Divorce” and signed with my name. As it happens, I did not write it. It is quite a worthy effort, as pastiches go, and particularly successful in re-producing my weaknesses. A second story, “Cannon,” also signed with my name, appears in the current issue of Voyages. As a candidate-member of the Scandinavian Institute of Comparative Vandalism,* I would rate the second item somewhat inferior to the first, but again, I am not responsible. . . .“Cannon!” also appeared in the Ann Arbor Review and in The Georgia Review; the editor of the latter oddly responded in defense that he had never before “read a story by Real-Barthelme.” As Barthelme’s biographer Tracy Dougherty notes, both hoaxes have some characteristic elements readers might expect, but they ultimately fall short: Barthelme’s “‘golden ear,’ is nowhere in evidence” and instead one finds “deliberately mixed metaphors and abstract phrasing without Don’s satiric intent.”

“The School,” published the summer after these hoaxes appeared, is unmistakably Barthelme—and is perhaps his most often reprinted story, ubiquitous in anthologies and in syllabi. In just a little more than 1,200 words, the tale describes an elementary school beset by a series of escalating disasters. “The sense of impending doom is macabre but somehow hilarious at the same time,” remarks Charles McGrath in the introduction to the recently published Library of America edition of Barthelme’s short stories. McGrath also comments on the finale’s unexpected hopefulness:

There are lots of such moments in Barthelme—not happy endings, exactly, but provisional ones, a hopefulness conjured sometimes out of nothing more than the author’s wish not to leave us (and himself) too far down in the dumps. For all his difficulty and occasional impenetrableness, Barthelme was at heart a generous writer who thought that his main task, especially in what he saw as a belated and diminished time, was to sneak up on the readers and startle them with a little dose of pleasure and surprise.The novelist T. Coraghessan Boyle, who introduces “The School” in one of those aforementioned anthologies, praises it as his favorite of Barthelme’s short works:

The question it poses is simple: What good is human knowledge (i.e., the lesson plan) in the face of the unknowable? The speaker, an elementary-school teacher, has, in following the rigid course laid out by the lesson plan, inadvertently taught his students not so much about the miracle of life as about its ineluctable conclusion. In large part, the comedy derives from the speaker’s laid-back language and lack of awareness in describing the increasingly absurd and ironic string of fatalities that collides head on with his best intentions.

* There is a real institute of that name behind Barthelme’s joke.

* * *

Well, we had all these children out planting trees, see, because we figured that . . . that was part of their education, to see how, you know, the root systems . . . and also the sense of responsibility, taking care of things, being individually responsible. . . . If you don't see the full selection below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!This selection is used by permission.

To photocopy and distribute this selection for classroom use, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center.