From Albert Murray: Collected Essays & Memoirs

Interesting Links

Video: “A Tribute to Albert Murray” on the 50th anniversary of South to a Very Old Place (Six Bridges Presents, YouTube)

“A ’73 Odyssey and a ’16 Home: Albert Murray and Harvard University” (Paul Devlin, Library of America)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Manifest Destiny U.S.A.,” Albert Murray

• “Harlem,” Ann Petry

• “The Great Eaters of Georgia,” Carson McCullers

Buy the book

Albert Murray: Collected Essays & Memoirs

Albert Murray: Collected Essays & Memoirs

The Omni-Americans | South to a Very Old Place | The Hero and the Blues | Stomping the Blues | The Blue Devils of Nada | From the Briarpatch File | more

List price: $45.00

Web store price: $27.00

Video: “A Tribute to Albert Murray” on the 50th anniversary of South to a Very Old Place (Six Bridges Presents, YouTube)

“A ’73 Odyssey and a ’16 Home: Albert Murray and Harvard University” (Paul Devlin, Library of America)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Manifest Destiny U.S.A.,” Albert Murray

• “Harlem,” Ann Petry

• “The Great Eaters of Georgia,” Carson McCullers

Buy the book

Albert Murray: Collected Essays & Memoirs

Albert Murray: Collected Essays & MemoirsThe Omni-Americans | South to a Very Old Place | The Hero and the Blues | Stomping the Blues | The Blue Devils of Nada | From the Briarpatch File | more

List price: $45.00

Web store price: $27.00

In 1967 Willie Morris had published the memoir North Toward Home, recalling his smalltown childhood in Mississippi, his young adulthood in Texas, and his life during the 1960s in New York City (including his close friendship with Ralph Ellison, who was also good friends with Murray). The book became a best seller and struck a chord with many Southerners who had moved north yet still felt nostalgic for the South. Two years after the book appeared, Morris suggested that Murray return to his own hometown of Mobile, Alabama, and write a magazine article about how things have changed in the wake of desegregation. Or that was the basic idea.

“Instead of going to Mobile,” Murray told Rowell, “I decided to go south, with Mobile included in it, Mobile being a point of return back north. . . . I’ll go south and stop in North Carolina, stop in Georgia, and then go by Tuskegee, go to Mobile, go to New Orleans, go to Greenville, Mississippi, and then stop in Memphis.” Supplied with an advance for travel expenses, he began the trip by heading north from his home in Harlem to New Haven, where he interviewed two well-known Southerners teaching at Yale: the historian C. Vann Woodward and the novelist Robert Penn Warren. He then went on his trip down South, meeting up with the novelist Walker Percy, the journalist Edwin M. Yoder Jr., and many Southern newspaper editors and reporters, as well as “homefolks” in Mobile. “I decided that I was not going to write a civil rights report or anything like that,” Murray explained. “I tried to make a poem, a novel, a drama—a literary statement—about being a Southerner.”

Although Murray may have strayed from the original “assignment,” he did so with Morris’s approval and support. In late 1970 Morris told an interviewer that Murray’s piece was “all written except for the last ten pages.” Paul Devlin, Murray’s assistant and close friend during the decade before his death, says that it isn’t known if the plan was to publish the article as a series or in a single issue of the magazine. In any case, the sixty-four-thousand-word result—part memoir, part interview-based journalism—never appeared in Harper’s, because Morris was fired just as Murray was finishing it. Fortunately, Murray already had a contract with McGraw-Hill for the project, and South to a Very Old Place appeared as a book in November 1971.

Shortly after it was published, a radio interviewer asked Murray, “Do you consider yourself a writer or a critic?” “A writer,” he answered without hesitation. “The critical work is just preliminary work for the creative work. I consider myself a maker of images. . . . The Omni-Americans would be considered a critical book—no, a critique of American culture, and it would be a counterstatement, whereas [South to a Very Old Place] is an attempt to create an image that would be a counterstatement—a counterimage.” Or, as he described his aim in the book itself: “the ever so newsworthy political implications would be obvious enough; and after all doesn’t anything that any black, brown, or beige person says in the United States have the most immediate political implications? No strain for that. But the overall statement would be literary—as literary, which is to say as much of a metaphorical net, as you could make it.”

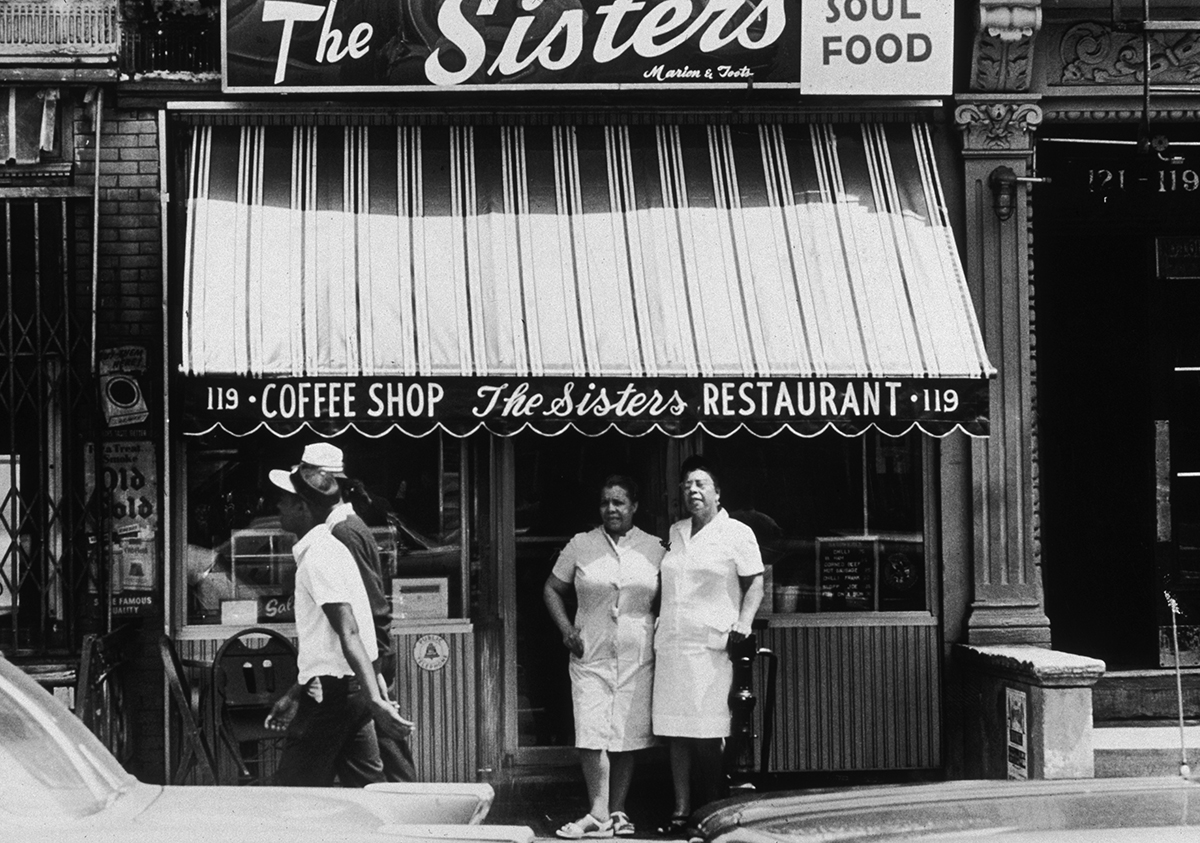

Near the end of North Toward Home Morris described one memorable gathering that occurred as he was finishing his book. “At Al Murray’s apartment in Harlem, on New Year’s Day 1967, the Murrays, the Ellisons, and the Morrises congregated for an unusual feast: bourbon, collard greens, black-eyed peas, ham-hocks, and cornbread—a kind of ritual for all of us. Where else in the East but in Harlem could a Southern white boy greet the New Year with the good-luck food he had had as a child?” Where else, then, could Murray’s “counterimage” of the South begin other than where he ended up—in Harlem, his home since 1962 and until his death in 2013? Or as Murray himself said, “When you take the ‘A’ train for Harlem you are heading north but also south and home again.” And so, for the 50th anniversary of South to a Very Old Place, we present the book’s prologue—Murray’s Southern ode to Harlem.

Notes: Murray mentions numerous Harlem landmarks and celebrities in his essay. The IND Station at 125th Street refers to a station of the Independent Subway System (today’s A–G lines), one of several New York City systems managed separately. The IND was owned by the city; the IRT (1–7 lines) was a privately owned system. The thirteen-floor Hotel Theresa, now repurposed as an office building, was the choice of Black celebrities in the 1940s and 1950s. Lenox Terrace is a postwar Harlem apartment complex (and, after 1962, Murray’s place of residence). The Schomburg Library referred to the New York Public Library building on West 135th Street that housed a significant collection of books and manuscripts of the African diaspora donated by Arthur A. Schomburg in the 1930s. Both the building and the collection are now part of the much larger Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Smalls Paradise was a Harlem nightclub. CCNY is the City College of New York. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was pastor of Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church and served as a U.S. congressman from 1945 to 1971. Buddy Bolden was a New Orleans–style cornet player. Billy Strayhorn wrote “Take the A Train” (1939), the signature tune of the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

Rowell’s interview from 1997, quoted in the introduction above, appeared in Callaloo, the literary journal he founded in 1976 and has edited ever since. Also quoted is a radio interview, which aired originally on the New York City program The World Today and was “re-broadcast” for the first time in half a century when Paul Devlin, coeditor of the two-volume Library of America edition of Murray’s writings, played it at the end of “A Tribute to Albert Murray,” a panel discussion that occurred on December 9, 2021. Other details of the above history about the book’s creation were also gleaned from Devlin’s presentation. The video can be viewed on YouTube; the radio interview with Murray begins at the 1:35:00 mark.

Rowell’s interview from 1997, quoted in the introduction above, appeared in Callaloo, the literary journal he founded in 1976 and has edited ever since. Also quoted is a radio interview, which aired originally on the New York City program The World Today and was “re-broadcast” for the first time in half a century when Paul Devlin, coeditor of the two-volume Library of America edition of Murray’s writings, played it at the end of “A Tribute to Albert Murray,” a panel discussion that occurred on December 9, 2021. Other details of the above history about the book’s creation were also gleaned from Devlin’s presentation. The video can be viewed on YouTube; the radio interview with Murray begins at the 1:35:00 mark.

* * *

For this week’s selection, we depart from the usual format and reproduce Murray’s piece, in its entirety, below. You may also download it as a PDF or view it in Google Docs.New York:

Tall Tale Blue Over Mobile Bay in Harlem

You can take the “A” train uptown from Forty-second Street in midtown Manhattan and be there in less than ten minutes. There is a stop at Fifty-ninth Street beneath the traffic circle which commemorates Christopher Columbus who once set out for destinations east on compass bearings west. But after that as often as not there are only six more express minutes to go. Then you are pulling into the IND station at 125th Street and St. Nicholas Avenue, and you are that many more miles north from Mobile, Alabama, but you are also, for better or worse, back among homefolks no matter what part of the old country you come from.

But then, going back home has probably always had as much if not more to do with people as with landmarks and place names and locations on maps and mileage charts anyway. Not that home is not a place, for even in its most abstract implications it is precisely the very oldest place in the world. But even so, it is somewhere you are likely to find yourself remembering your way back to far more often than it is ever possible to go by conventional transportation. In any case, such is the fundamental interrelationship of recollection and make-believe with all journeys and locations that anywhere people do certain things in a certain way can be home. The way certain very special uptown Manhattan people talk and the way some of them walk, for instance, makes them homefolks. So whoever says you can’t go home again, when you are for so many intents and purposes back whenever or wherever somebody or something makes you feel that way.

There is also the “D” train which you can take from Forty-second Street over on Sixth Avenue, because that way you still come into the “A” train route at Columbus Circle. Or you can take Number Two or Number Three on the IRT, and the uptown Avenue will be Lenox, and if you get off at 125th Street you walk west to the old Theresa Hotel corner at Seventh, the Apollo near Eighth, and Frank’s Chop House, on over toward St. Nicholas. At the 135th Street IRT stop you come out at the northwest corner of Lenox Terrace, and you are also at the new Harlem Hospital. From there, which is only a few steps from the AME Church that used to be the old Lincoln Theatre, you walk east to Riverton, Lincoln, and the water. But for the Schomburg Library, the YMCA poolroom, and Smalls Paradise, you walk west toward the hill and CCNY.

Sometimes, of course, all you need to do is hear pianos and trumpets and trombones talking, in any part of town or anywhere else for that matter. Or sometimes it will be pianos and saxophones talking and bass fiddles walking; and you are all the way back even before you have time to realize how far away you are supposed to have gone, even before you become aware of even the slightest impulse to remember how much of it you thought perhaps you had long since forgotten.

Sometimes it can be downhome church organs secularized to Kansas City four-four in a neighborhood cocktail lounge. It can be a Count Basie sonata suggesting blue steel locomotives on northbound railroad tracks (as “Dogging Around” did that summer after college). It can be any number of ensemble riffs and solo licks that also go with barbershops and shoeshine parlors; with cigar smoke and the smell and taste of seal-fresh whiskey; with baseball scores and barbecue pits and beer-seasoned chicken-shack tables; with skillets of sizzling mullets or bream or golden crisp oysters plus grits and butter; and with such white potato salads and such sweet potato pies as only downhome folks remember from picnics and association time camp meetings. Or it can even be a stage show at the Apollo Theatre which sometimes rocks like a church during revival time. It can be the jukebox evangelism of some third-rate but fad-successful soul singer (so-called) that carries you back not only to Alabama boyhood Sundays with sermons followed by dasher-turned ice cream, but also to off-campus hillside roadside beer joints and Alabama pine-needle breezes.

So naturally it can also be Lenox Avenue storefront churches, whether somewhat sedate or downright sanctified. Or it can be the big league uptown temples along and off Seventh Avenue: such as, say, Big Bethel, Mother Zion, Metropolitan, Abyssinian Baptist, where on the good days Adam Clayton Powell, for all his northern-boy upbringing, sounds like Buddy Bolden calling his flock.

None of which is to suggest—not even for one sentimental flicker of an instant—that being back is always the same as being where you wish to be. For such is the definitive nature of all homes, hometowns, and hometown people that even the most joyous of homecoming festivities are always interwoven with a return to that very old sometimes almost forgotten but ever so easily alerted trouble spot deep inside your innermost being, whoever you are and wherever you are back from.

For where else if not the old home place, despite all its prototypical comforts, is the original of all haunted houses and abodes of the booger man? Indeed, was even the cradle only a goochie-goochie cove of good-fairy cobwebs entirely devoid of hobgoblin shadows; or was it not also the primordial place of boo-boo badness and doo-doo-in-diapers as well?

Once back you are among the very oldest of good old best of all good friends, to be sure, but are you not also just as likely to be once again back in the very midst of some snarled-up situation from which you have always wanted to be long gone forever?

And where else did you ever in all your born days encounter so much arrogant ignorance coupled with such derisive mockery and hey-you who-you crosstalk? Where else except in this or that Harlem are you almost always in danger of getting kicked out of a liquor store for instance for browsing too casually in the wine section. Where else except among homefolks is that sort of thing most likely to tab you not as an expense-account gourmet-come-lately but a degenerate wino? Or something worse.

***

But still and all and still in all and still withal if there are (as no doubt there have always been) some parts of Harlem where even such thugs and footpads as inhabited the London of Charles Dickens would probably find themselves more often mooched and mugged than mooching and mugging so are there at least one thousand plus one other parts and parcels also. Not to mention such browngirl eyes as somehow can always make even the smoggiest New York City skies seem tall tale blue over Mobile Bay.

Naturally there are those who not only allege but actually insist that there can only be ghetto skies and pathological eyes in Harlem and for whom blues tales are never tall but only lowdown dirty and shameful. But no better for them. They don’t know what they’re missing. Or don’t they? For oh how their pale toes itch to twinkle as much to the steel blue percussion as to all the good-time moans and the finger-snapping grunts and groans in Billy Strayhorn’s ellington-conjugated nostalgia.

From SOUTH TO A VERY OLD PLACE by Albert Murray. Reprinted by permission of Vintage Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 1971 by Albert Murray.

This selection is used by permission. To photocopy and distribute this selection for classroom use, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center.

This selection is used by permission. To photocopy and distribute this selection for classroom use, please contact the Copyright Clearance Center.