From The Black Fantastic: 20 Afrofuturist Stories

Interesting Links

“On Fantasy and the Poetry of the Past: An Interview with Sofia Samatar” (Safwan Khatib, Word Without Borders)

“Radium: Topics in Chronicling America” (Library of Congress)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Frog Pond,” Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

• “Sisters and Science Fiction,” Karl Kroeber • “The Fog” Berton Roueché

• “Of Man and the Stream of Time” Rachel Carson

Buy the book

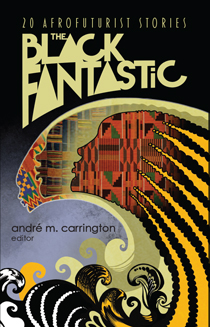

The Black Fantastic: 20 Afrofuturist Stories

The Black Fantastic: 20 Afrofuturist Stories

Paperback | 376 pages

List price: $24.95

Web store price: $19.95

revealed to another interviewer. “Whatever group that I'm in, I might, you know, tend to be kind of the odd one.”“On Fantasy and the Poetry of the Past: An Interview with Sofia Samatar” (Safwan Khatib, Word Without Borders)

“Radium: Topics in Chronicling America” (Library of Congress)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Frog Pond,” Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

• “Sisters and Science Fiction,” Karl Kroeber • “The Fog” Berton Roueché

• “Of Man and the Stream of Time” Rachel Carson

Buy the book

The Black Fantastic: 20 Afrofuturist Stories

The Black Fantastic: 20 Afrofuturist StoriesPaperback | 376 pages

List price: $24.95

Web store price: $19.95

Her father, Said Sheikh Samatar, was born probably in 1943 (there are no birth documents) and “probably under an acacia tree” (as he put it). He spent his childhood as a camel-herder in the Somali region of Ethiopia; when he was sixteen his father allowed him to attend an elementary school to learn to read and write alongside students half his age. At twenty, Said went to Mogadishu, where he held a job and took a night class in English taught by Lydia Glick, who was then with the Mennonite Mission in Somalia; he in turn helped her learn the Somali language. In 1965, about 22 years old, Said returned to Ethiopia to enroll in high school and four years later went back to Somalia, where he and Lydia renewed their friendship. In 1970 they married in both Christian and Muslim ceremonies and went to the United States after Said received a scholarship at Goshen College, a private Mennonite college in Indiana.

Sofia was born the following year. Her childhood was spent moving from Indiana, to Illinois, to Tanzania, to London, to Kentucky. Along the way, Said earned his PhD in African history at Northwestern University. Sofia told Publishers Weekly that her parents’ “relationship was kind of steeped in language and literature. We moved from place to place, but we always had our books.” The family moved to New Jersey when, in 1981, Said was hired by Rutgers University, where he rose to full professor and became one of the world’s most eminent authorities on the history of Somalia. He died in 2015.

While her family settled down near Rutgers, Sofia enrolled in a Mennonite high school in Pennsylvania and, following her father’s footsteps but not his advice, then went on to Goshen College. (He had urged her to attend an Ivy League school.) At Goshen, Samatar studied under one of her father’s professors, Ervin Beck, who introduced her to the works of Gabriel Garcia Márquez and Salman Rushdie, among other authors. At the University of Wisconsin–Madison, she earned a Master’s in African language and literature and a PhD in Arabic literature. In the years between her graduate degrees, she married fellow writer Keith Miller, an American born in Tanzania, and they lived for three years in Sudan and nine years in Egypt, teaching English. She and her husband now live in Virginia, where she is a professor at James Madison University.

Samatar’s background and experiences have profoundly influenced her writing: novels, stories, poems, essays, memoirs, and more. Although she has become known mostly for her fantasy fiction, much of her work defies genre. As she explained to Alicia Cole at Black Fox Magazine:

I’m always trying to merge things, rather than balance them. I want to create new things that are mixtures of genres or categories I’ve been told are incompatible. I hate separations and borders—I’m always trying to break them down. This has a lot to do with race, of course, with being a person of mixed race, and a person of two different cultures. In my position, you have to believe that boundaries can be broken down, that so-called opposites can merge.In a recent book, Opacities: On Writing and the Writing Life, she elaborates:

I had already learned, as a writer of fantasies, a genre writer, as people said, that eventually, in writing fantasy and science fiction, one runs smack up against the problem of the code. The code is the structure demanded by the genre: what makes a work recognizable as science fiction, thriller, or romance. . . . I had begun to feel hampered by these codes, and to despair of subverting them, although I still loved fantasy and science fiction. . . .“To be the Bartleby is to be the alien,” she adds, preferring not to stay within the boundaries of genre and in each work creating a fusion of styles. She has noted elsewhere that this aspect of her work is what made her debut novel, A Stranger in Olondria, “so hard to sell. It mingles the tropes of epic fantasy with language that’s unusual for the genre today.” She could not find a publisher for it for more than five years, yet it won the World Fantasy and British Fantasy awards for Best Novel.

With its blend of futurism, history, and family drama, “Tender,” the title story of Samatar’s first collection of short fiction, similarly bends the “code” of science fiction. The tale’s narrator serves the community by separating herself from it, standing guard over a facility where she oversees the storage of radioactive waste. She has become an outsider—a literally toxic misfit living behind glass “not to protect me from contamination by the outside world, but to protect the world from me.”

Notes: Samatar intersperses mentions of and quotations from various sources. Conference of the Birds is a Persian poem by the Sufi mystic Attar of Nishapur (Farid ud-Din Attar, c. 1145–c. 1221). The quotation from Isidor Isaac Rabi is from a speech given at the Boston Institute for Religion and Social Studies on January 3, 1946. The quotation from Robert Oppenheimer is from “Physics and the Contemporary World,” a lecture Oppenheimer presented at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on November 25, 1947. Abba Moses was an ascetic priest of Roman Egypt; he was quoted in the fifth-century Apophthegmata Patrum (Sayings of the Desert Fathers).

* * *

I am a tender. I tend the St. Benedict Radioactive Materials Containment Center. . . . If you don't see the full selection below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!This selection may be photocopied and distributed for classroom or educational use.