From Willa Cather: Stories, Poems, & Other Writings

Interesting Links

“Explore the World of Willa Cather in Her Nebraska Hometown” (Jeff MacGregor, Smithsonian Magazine)

“Never-Ending Nostalgia: Who and What Inspired Willa Cather” (Benjamin Taylor, LitHub)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Peter,” Willa Cather

• “The Circus at Denby,” Sarah Orne Jewett

• “Bill of Fare on the Plains,” Annie D. Tallent

Buy the book

Willa Cather: Stories, Poems, & Other Writings

Willa Cather: Stories, Poems, & Other Writings

Alexander’s Bridge | My Mortal Enemy | 28 stories | essays and reviews | poems | 1,039 pages

List price: $45.00

Web store price: $31.50

Buy all three Willa Cather volumes in a boxed set and save $45

“Explore the World of Willa Cather in Her Nebraska Hometown” (Jeff MacGregor, Smithsonian Magazine)

“Never-Ending Nostalgia: Who and What Inspired Willa Cather” (Benjamin Taylor, LitHub)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “Peter,” Willa Cather

• “The Circus at Denby,” Sarah Orne Jewett

• “Bill of Fare on the Plains,” Annie D. Tallent

Buy the book

Willa Cather: Stories, Poems, & Other Writings

Willa Cather: Stories, Poems, & Other WritingsAlexander’s Bridge | My Mortal Enemy | 28 stories | essays and reviews | poems | 1,039 pages

List price: $45.00

Web store price: $31.50

Buy all three Willa Cather volumes in a boxed set and save $45

In 1899, Wisconsin-born Hamlin Garland, who had spent most of his early years living with his family on homesteads in South Dakota and Iowa, published Boy Life on the Prairie, a collection of semi-autobiographical sketches about rural life. In one chapter, he described the importance each summer of the traveling circus:

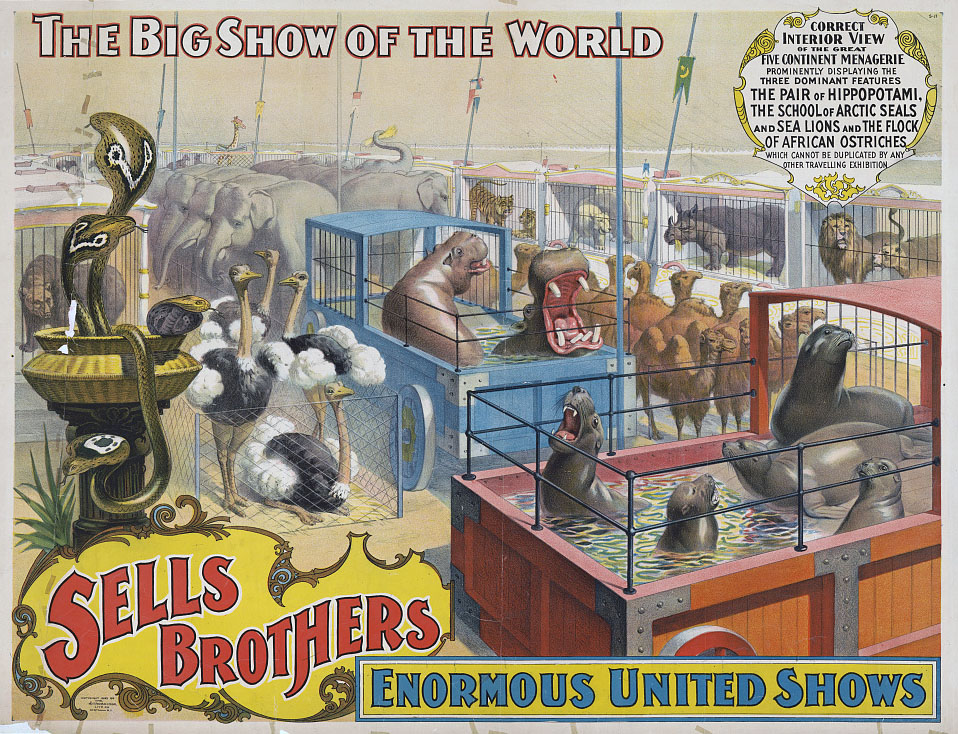

No one but a country boy can rightly measure the majesty and allurement of a circus. To go from the lonely prairie or the dusty corn-field and come face to face with the “amazing aggregation of world-wide wonders” was like enduring the visions of the Apocalypse. From the moment the advance man flung a handful of gorgeous bills over the corn-field fence, to the golden morning of the glorious day, the boys speculated and argued and dreamed of the glorious “pageant of knights and ladies, glittering chariots, stately elephants, and savage tigers,” which wound its way down the long yellow posters, a glittering river of Elysian splendors, emptying itself into the tent, which housed the “World’s Congress of Wonders.”“The boy whose father refused to take him wept with no loss of dignity in the eyes of his fellows,” Garland recalled. “He could even swear in his disappointment and be excused for it.”

The year after the book appeared, Willa Cather published “The Sentimentality of William Tavener” in The Library, a new Pittsburgh literary magazine that employed her as a staff writer and editor. Her short story opens with the distress exhibited by the sons of a farmer who has denied them permission to take a day off from their farm chores to go to the circus.

The timing may well be a coincidence; circuses featured frequently in stories and novels of the era. Indeed, there is no way to confirm that Cather was inspired to write her story by Garland’s chapter on circuses or, for that matter, that she had even yet read it—although she clearly kept up with his work. Five years earlier, in 1895, she mockingly panned a “love story” by the editor of the Lincoln Courier and joked that she felt obliged to read it because any local tale might prove to be “the forerunner of many valuable additions to Mr. Hamlin Garland’s western school of literature.”

Cather was referring to Garland’s series of influential essays, which were collected the previous year in book form as Crumbling Idols. Garland advocated for a ”new school” of literary realism “true to the scenes and the people we love” in “the interior of America,” but he antagonized many in the literary world by inveighing against the dominance of tradition-bound publishers, editors, and critics in New York and Boston: “By what right do you of the conservative East assume to be final judges of American literature?” Although Garland continued to write about farm life and the American West, in 1902 he surrendered to the realities of the marketplace and, in order to work more closely with his editors and publishers, began spending much of each year in New York City, where he stayed until 1930. Cather, too, moved to New York in 1906 and lived there for the rest of her life. (Garland and Cather apparently did not meet each other until 1919 or 1920.)

Several scholars and critics have noted how some of Cather’s early stories resemble Garland’s tales and sketches; biographer James Woodress refers to her apprentice work about prairie life, including “The Sentimentality of William Tavener,” as written in “her Hamlin Garland manner.” Yet Mildred R. Bennett, author of The World of Willa Cather, contends that the Tavener story stands out: “its economical, low-keyed narrative style distinctly suggests the author’s later manner.” Marilyn Arnold, in her book about Cather’s short fiction, agrees: “Cather’s growing sense of how much to say and how much to leave unsaid, her increasing skill at delineating a character with one stroke, her almost uncanny ability to define a relationship with a single apt observation, and her marvelous feeling for low-keyed humor are evident.”

Some scholars have also asserted that the story is autobiographical and have pointed to Woodress’s reference to its “rather skillful use of what must have been a family story.” Although the story certainly has autobiographical elements, Woodress didn’t provide any evidence to support his supposition. Like the Taveners, Cather’s parents migrated from the Shenandoah Valley, and perhaps they both went to a circus before they were married. Yet, just as certainly, the story does not depict Cather’s immediate family. Her father, Charles Cather, didn’t last long as a Plains farmer; he sold out after a mere eighteen months in Nebraska and moved his family to Red Cloud in 1884. Futhermore, only two of Willa’s four brothers had been born, and they turned four and seven years old that year—hardly old enough to be the farmhands described in the story. While there were plenty of farms in the region that were homes to children working long days without end, deprived of festivities, the Cathers could not count themselves among them. In August 1888, after Willa had been living in Red Cloud for four years, she wrote to a friend: “We children have a great many picnics, parties & circus’ this summer.”

Notes: “The Sentimentality of William Tavener” is the only work by Willa Cather that is set in both Virginia, where she was born, and Nebraska, where she lived after she was nine years old. The Taveners’ farm, however. is in McPherson County, which is 200 miles northwest of the Cather home in Red Cloud. Like the Cathers, William and Hester Tavener migrated from the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Back Creek runs ten miles to the west of the city of Winchester, and Romney is 30 miles further, West Virginia. Cather’s last novel, Sapphira and the Slave Girl, takes place in this same region in Virginia.

* * *

It takes a strong woman to make any sort of success of living in the West, and Hester undoubtedly was that. . . . If you don't see the full selection below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!This selection may be photocopied and distributed for classroom or educational use.