From Shakespeare in America: An Anthology from the Revolution to Now

Interesting Links

“How Vaudeville Told the Story of America . . . to Americans” (Geoffrey Hilsabeck, LitHub)

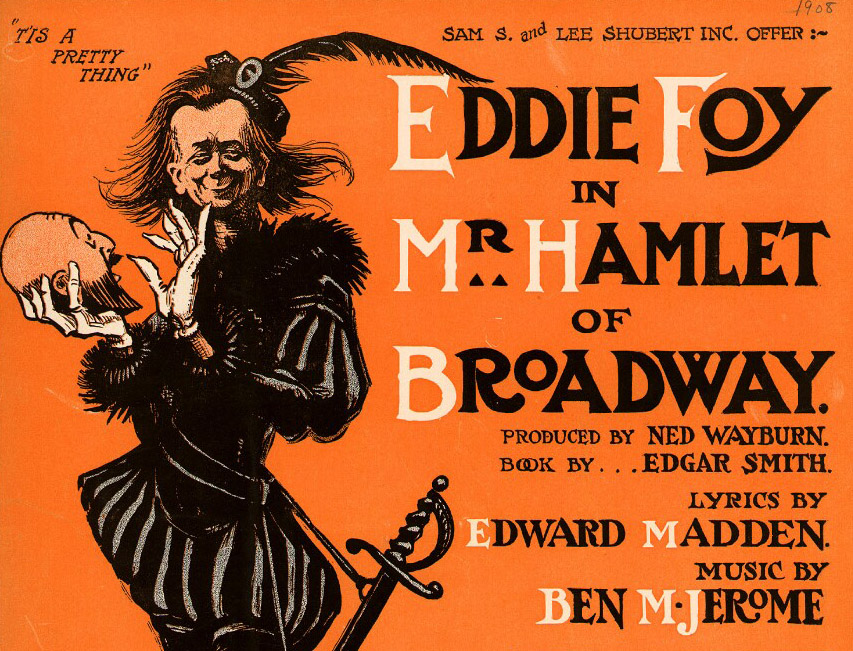

“Play It Again, Ham [on Eddie Foy and Hamlet]” (Rachel B. Dankert, The Collation, Folger Shakespeare Library)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “The Life and Death of Vaudeville,” Fred Allen

• “Melodrama,” Rollin Lynde Hartt

• “The Hiartville Shakespeare Club,” Belle Marshall Locke

Buy the book

Shakespeare in America: An Anthology from the Revolution to Now

Shakespeare in America: An Anthology from the Revolution to Now

List price: $35.00

Save 35%, free shipping Web store price: $22.75

“How Vaudeville Told the Story of America . . . to Americans” (Geoffrey Hilsabeck, LitHub)

“Play It Again, Ham [on Eddie Foy and Hamlet]” (Rachel B. Dankert, The Collation, Folger Shakespeare Library)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “The Life and Death of Vaudeville,” Fred Allen

• “Melodrama,” Rollin Lynde Hartt

• “The Hiartville Shakespeare Club,” Belle Marshall Locke

Buy the book

Shakespeare in America: An Anthology from the Revolution to Now

Shakespeare in America: An Anthology from the Revolution to NowList price: $35.00

Save 35%, free shipping Web store price: $22.75

Days after his “discovery,” Georgie was escorted to a concert hosted by Caruso at Wallack's Theatre in Times Square to benefit the family of slain police officer Joseph Petrosino. After the famous tenor performed, Edwards sang his new satirical hit “My Cousin Caruso” and then, keeping with the theme, Georgie made his stage debut with a spot-on parroting of Edwards imitating the opera star, an act greeted with wild ovations and encores, after which a triumphant Caruso hoisted the boy on his shoulder and carried him off the stage. Georgie moved in with Mary and Gus Edwards and became a star performer in various Edwards revues; his parents received his $10 weekly salary. That summer, singing as a stooge in the audience, Georgie introduced to the world the Gus Edwards & Edward Madden megahit “By the Light of the Silvery Moon” in the annual vaudeville revue School Boys and Girls at Hammerstein’s Victoria Theatre, weeks before the song was made even more famous by Lillian Lorraine in Ziegfeld Follies of 1909. He remained with the Edwards team until 1917, when he struck out on his own.

When Price was 22 years old, he met up with Lorenz Hart and Morrie Ryskind. Years earlier he had bought material for a comedy act from Lorenz through an agent, and he was now looking for a new sketch to try out at a vaudeville theater in Brooklyn. According to Gary Mormostein’s biography of Hart, when the two writers delivered the skit, “Shakespeares in 1922,” Price agreed to use it but insisted that they not attend because they would make him nervous. The writers went secretly, paid for seats in the gallery, and observed the audience’s enjoyment of Price’s performance of their material. The next day Price, not realizing his success had been witnessed, tried to convince the pair that the skit didn’t go over well and offered the two men $100 for their work—a ploy that initially caused Ryskind to lose his cool and refuse the payment until Hart talked him down. They took the money and Price continued using the act throughout the year.

In the sketch, Price plays five Shakespearean characters. Each role begins with an introductory refrain, followed by a condensed, over-the-top spoof of a soliloquy and ending with a burlesque of one of Jonson’s hits: Shylock sings a parody of “The Spaniard That Blighted My Life”; Hamlet sings “My Mammy”; King Lear, “April Showers”; Mark Antony, “After the Ball”; and Romeo, “Yoo-Hoo.” Since Price was well known for his imitations of (and rivalry with) Jolson, his performance would have made comedy from the very idea of Al Jolson playing various Shakespearean roles.

Vaudeville has a reputation as a lowbrow art for a rough-hewn audience, but the profusion of Shakespearean parodies in productions ranging from minstrel acts to Ziegfeld extravaganzas demonstrates that variety show audiences knew their Shakespeare—and knew it well. Price recalled how, when he was growing up, the noted stage actor “E. H. Sothern spent many hours with me perfecting the accents, inflections, and intonations used in some of his Shakespearean roles.” Hart and Ryskind’s sketch for Georgie Price, remarks theater historian Frances Teague, “invites the audience both to preen itself on cultural sophistication, and to sneer at both the stuffiness of high culture and the vulgarity of low. The audience laughs at Shakespeare’s simultaneous presence and absence from the stage, at the pretense that he must be an agent for respectability when such agency is displaced into colloquial jokes.” Or, as the vaudevillian Shylock says, “The plays will look like new / When I add a song or two.”

* Price was born on January 5, 1900, and his actual age (as with most child actors of the era) was a matter for confusion that he seemed to have encouraged for the rest of his life; a capsule biography provided during his radio days in the 1930s claimed “he was ‘discovered’ by Gus Edwards at the age of five”—four years before the verifiable events that launched his career. Some of the details of Price’s early life are taken from an unfinished memoir written in the 1950s; the document was uploaded to a website two decades ago by his son Marshall Price.

Notes: Antonio is Shylock’s nemesis in The Merchant of Venice and Alphonso Spagoni is the bullfighter in Al Jonson’s song “The Spaniard That Blighted My Life”; thus the name Antonio Spagoni in the parody of the song. Baseball commissioner Kenesaw Landis fined Babe Ruth $3,500 and suspended him for the first six weeks of the 1922 season after he violated the league’s rule against post-season barnstorming games. After his ill-fated barnstorming tour, Ruth signed with the B. F. Keith Circuit for a vaudeville show at New York’s Palace Theatre, where he participated in comedy sketches and performed a song written for him: “Little by Little and Bit by Bit, I Am Making a Vaudeville Hit!” Nella Melba was a world-famous soprano from Australia; Mary Garden was a Scottish American soprano.

* * *

Broadway has a Shakespeare fad,Actors all are Shakespeare mad. . . .

If you don't see the full selection below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!

This selection may be photocopied and distributed for classroom or educational use.