From Stephen Crane: Prose & Poetry

Interesting Links

“The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky,” 1952 adaptation, screenplay by James Agee, starring Robert Preston & Marjorie Steele (YouTube)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “An Experiment in Misery,” Stephen Crane

• “When Man Falls, a Crowd Gathers,” Stephen Crane

• “When I Knew Stephen Crane,” Willa Cather

Buy the book

Stephen Crane: Prose & Poetry

Stephen Crane: Prose & Poetry

Includes The Red Badge of Courage, Maggie, George’s Mother, The Third Violet, “The Monster,” stories, journalism, poetry, more

1,379 pages

List price: $50.00

Web store price: $35.00

“The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky,” 1952 adaptation, screenplay by James Agee, starring Robert Preston & Marjorie Steele (YouTube)

Previous Story of the Week selections

• “An Experiment in Misery,” Stephen Crane

• “When Man Falls, a Crowd Gathers,” Stephen Crane

• “When I Knew Stephen Crane,” Willa Cather

Buy the book

Stephen Crane: Prose & Poetry

Stephen Crane: Prose & PoetryIncludes The Red Badge of Courage, Maggie, George’s Mother, The Third Violet, “The Monster,” stories, journalism, poetry, more

1,379 pages

List price: $50.00

Web store price: $35.00

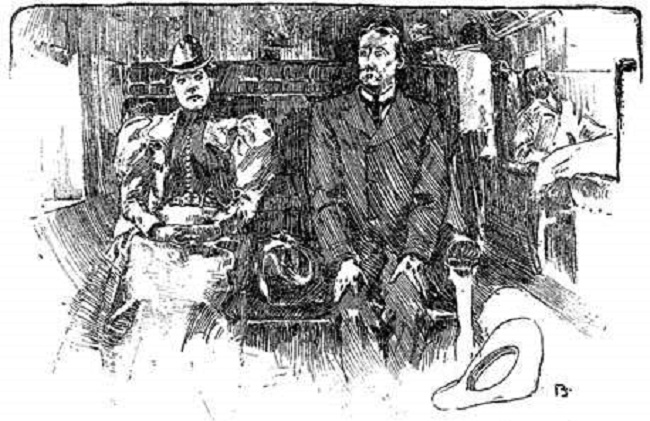

“The Bride of Yellow Sky” is the only story of the four that contains comic overtones. (James Agee played up the story’s humor in the screenplay he wrote for the second half of “Face to Face,” a double-bill feature film released in 1952.) Following a trip to Texas, Crane drafted this parody of the familiar Wild West formula pitching a sheriff against an outlaw. The upright marshal of Yellow Sky, nervously preparing to introduce his new bride to the “innocent and unsuspecting” town, returns from San Antonio in a sleek, modern Pullman train. The town’s drunken gunslinger, however, is a well-worn stereotype—an artifact of the dying, male-only frontier spirit. “As Crane makes clear,” notes the scholar James B. Colvert, the gunman is “a creation of the legend-mongering Eastern imagination, just as his costume is largely a creation of the New York garment industry,” and his relevance to the town is called into question when he comes face to face with its future. In the opening of her book On Writing, Eudora Welty describes what makes the story work so well by focusing on this conflict: “Two predicaments meet here. . . . You might say they gravitate towards each other—and collide. . . . Here are the plainest elements of comedy, two situations in a construction simple as a seesaw.”

Note: A drummer is a traveling salesman.

* * *

The great Pullman was whirling onward with such dignity of motion that a glance from the window seemed simply to prove that the plains of Texas were pouring eastward. . . . If you don't see the full story below, click here (PDF) or click here (Google Docs) to read it—free!This selection may be photocopied and distributed for classroom or educational use.